From My Mango Tree

by

Luther G. Strasen

(Updated in 2006)

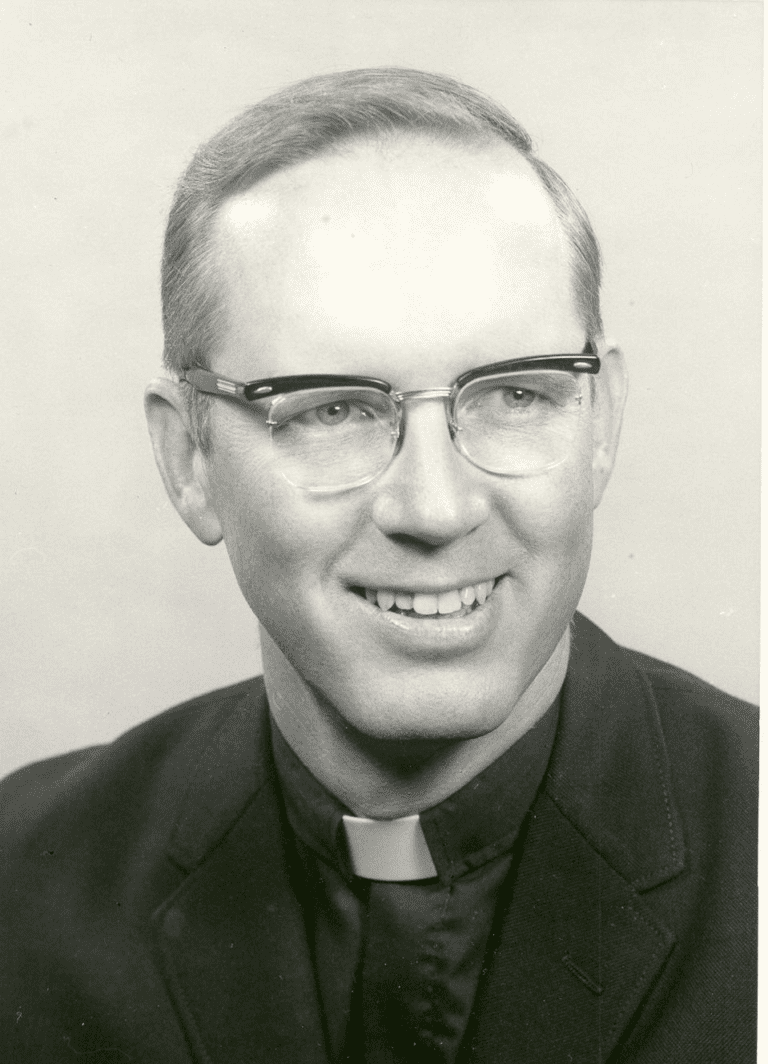

The Auto-biography of Luther George Strasen

<>< <>< <><

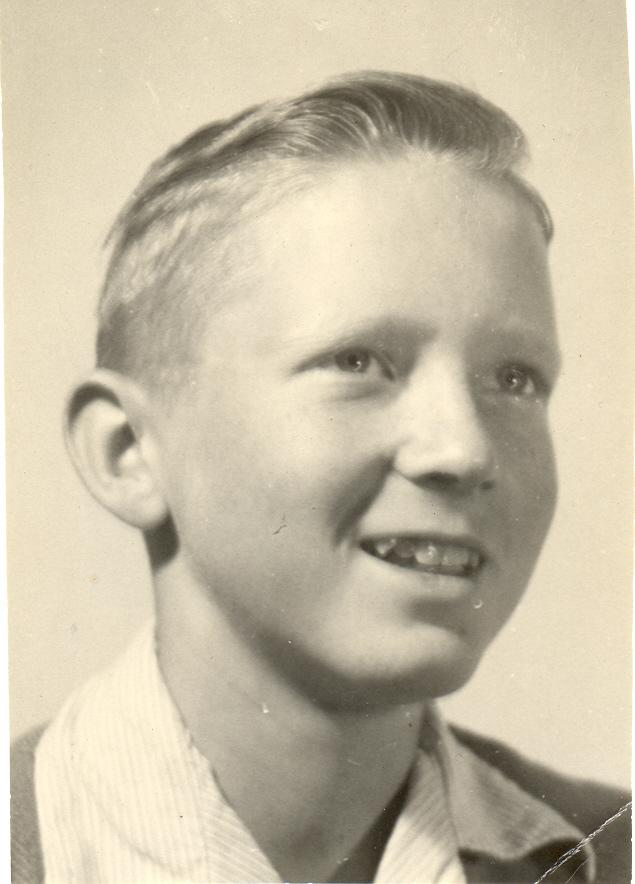

Chapter Two – The Sprout

When my Dad’s furlough in the United States ended, our family, except for Polly and Ruth, went back to India during the summer of 1939. Europe was erupting with hostilities that eventually became the Second World War, and Dad was directed by the Board of Missions to go to San Francisco to return to India by way of the Pacific Ocean. Polly and Ruth remained in the States to attend Milwaukee Lutheran High School (LHS). Ruth had skipped a year of school in India and so they both entered the freshman year. The next year they both transferred to the high school department of Dr. Martin Luther College, New Ulm, Minnesota, not far from Dad’s relative’s in Courtland, but returned to LHS for the senior year. They lived in dormitories during the school terms and in the summertime with relatives, or they worked for hire on farms near Janesville, Minnesota.

There was enough time before the embarkation date for a leisurely trip to the west coast. Dad took a southern route and we viewed Carlsbad Caverns, the Painted Desert and Petrified Forest, and the Grand Canyon. I already had a sense of direction. Dad became lost in San Francisco during some sight seeing and little five-year-old me directed him back to the Golden Gate Bridge. On the trip to India, on the S.S. President Adams, we made port at Kobe, Japan, Hong Kong, Manila in the Philippine Islands, and Singapore, finally arriving at Colombo, Ceylon. From there we traveled to the southern mainland of India by ferry and to Nagercoil by train and bus.

At this point in my life my memories are clearer. When we arrived in Nagercoil in 1939 there were more missionaries than there were mission-owned homes available and so houses were rented elsewhere. We lived in a compound on the Water Tower Road, about a half a mile east of the mission compound where I had spent the first years of my life. There were no house numbers on Water Tower Road, instead each house was given a name. Ours was “The Anchorage” and it was next door to “God’s Grace,” where missionary Robert Zorn’s family lived. There’s a story that one of my brothers got into an argument with a Zorn child and threatened to “lock him up in God’s Grace.”

The Board of Missions had rented The Anchorage from an Indian, Mr. Malachi, who also owned two compounded houses directly north of ours and lived in the one farthest from us. He was a Christian, with membership in the London Mission Society. I enjoyed visiting with Mr. Malachi. He gave me books to read with many pictures, such as one by the then famed African explorer couple, Martin and Osa Johnson. Some of the books’ covers had tunnels where bookworms had once eaten the cardboard and Mom didn’t relish the idea of the worms, figuring they were still there. Mr. Malachi died one day and the news was brought to our home in hushed tones. I wasn’t allowed to view him or attend the funeral, though I must have been ten years or older. The Malachi’s had a lovely daughter named Mercy, who was married on January 4, 1945, after her father’s death. Following the usual Indian customs, the marriage was arranged and she only saw pictures of her husband before the wedding day. On that day the groom, escorted by relatives, friends, and musicians, processed past our house on his way to escort her to the church. Our family went to the wedding and also to the sumptuous curry feasts that were prepared at her house the night of the wedding and at his parents’ home the next noon.

The Anchorage, pictured here, was a much smaller compound than that of my first home on the mission compound. There was one entrance to the walled-in property, a double gate in the middle of the front wall, through which Dad’s Model A Ford could be driven. The gate kept out wandering cows, and also beggars. Certain days must have been “beggar days,” as there would be a stream of beggars on one day and then not again for some time. One of our servants, about whom I’ll write later, would hand out food on the current beggar day. As one faced the house, it was set back about thirty feet in the front right half of the property, with trees, croton bushes, and other flora around it, except on the side that ran down the middle of the property. In the front left corner of the property there was a one-car garage shaded by trees. In the middle left half of the property, Dad had meticulously constructed a croquet court of hard packed, leveled soil so that he could play the game at his leisure. Dad had played a great deal of tennis when we lived on the missionary compound (and where there were tennis courts), but now, in his forties, he wasn’t so vigorous.

To the left of the croquet court was a large mango tree inside the wall that separated our house from God’s Grace. It wasn’t only a tree for us to climb and play in, but it also housed red ants that stitched together the mango leaves for their nests, maybe three feet or more in circumference, filled with worker ants and white eggs. My playmates and I sometimes climbed up near a nest to smash it with sticks and watch the contents stream to the ground, at the same time trying to evade the stings of the enraged ants as some fell on us. The final back third of the property wasn’t as well groomed as the front. In the farthest back corner, behind the croquet court, was the servants’ “cacoose” – a latrine, about which I’ll write more. Behind the house there was an open well with a waist-high wall around it, more trees, and a shed where we kept chickens and, for a time, a water buffalo, for its milk.

The house was upper class (we lived better than most people in Nagercoil), though it had marked differences to homes in the States. It was quite impressive, with two floors, shaped in a rectangular, the front and the back of the house on the narrow ends. The second-floor space, however, was T-shaped, with two front bedrooms, one at each end of the top of the T, and an inner staircase space that then extended to the back through a door to provide a large storage space. The house walls were built of granite, covered with whitewashed plaster both inside and out. The pitched roof was a wooden framework over which dark-orange glazed earthen tiles were set in tiers. The room ceilings were at least nine feet high and all the floors were laid with porous, brownish tiles that could easily be washed, as they quickly absorbed water. I know that because Dad assigned portions of the floor for me to wash. Ruth has told me that she was given similar assignments. When I asked him why I had to do it, he told me that it was good for me to do menial labor. And that was all right, because it taught me that, even as a pastor, I didn’t have to consider myself above physical labor, such as cleaning the snow from sidewalks at my future parish at Greenwood, Indiana, when arriving first on a Sunday morning.

Each floor of The Anchorage had a veranda in the front that extended across two-thirds of the building, starting on the left, with only the upper veranda railed in. The lower veranda stood three or four feet above the ground with steps from the ground at the house’s center. (On those steps we sat and watched when Dad would engage a snake charmer. The man, squatting below us on the ground level, piped tunes to cobras that would rise from baskets and sway about.) From the first floor verandah a tall double door opened into a windowless long room that dominated the center of the building, extending two-thirds of the length of the house. Half way down, on the left wall, a stairway to the second floor rose toward the front of the house On the outside of the interior room were windowed rooms, a living room and bedroom on the left, and Dad’s study, another bedroom and a toilet room on the right, each with a doorway from the middle room. The back half of the interior room, set with a dining table and chairs, was where we ate all our meals. The living room, at the front left, had windows that opened to the veranda and to the side. Dad’s study, first room on the right, had the same amount of windows, but was larger because it took up the space in the front where the other third of the veranda would have been. The back third of the house, to which more doors at the far back of the long middle room opened, contained the pantry and kitchen area on the left and another windowless room in the middle where clothes were prepared before and after they were washed. To the right of it were two rooms for bathing and dressing. A small roofless court, reached from both the kitchen and the clothes room, separated the kitchen from the bath area and had a trellised entryway to the outside.

One upstairs bedroom was above the living room and so had the upper veranda outside its front windows. We children had various sleeping arrangements that changed, but after Ted and Betty left for the States, as I’ll relate later, Dave and I both slept there. The windows of the Anchorage had no glass or screens; instead, there were bars and shutters.

So each bed had a framework from which mosquito netting was suspended so that its ends could be tucked under the mattress and we could sleep safe from the bites of the free-to-fly-anywhere insects. That’s why we also appreciated the “pollys” – small lizards that would frequent the walls, though not in any great number, and eat insects that were flitting about. Dad and Mom’s bedroom was above his study, with two large beds in it. Sometimes I would come into their bedroom in the morning and find them in a bed together, but at that age never grasped what that all was about. The large second-floor storage room that went down the spine of the house to the back, above the lower interior rooms, was essential, as there were no built in closets in the house. However, the bedrooms and bathing area had “almirahs” – stand alone, tall wooden closets.

The Anchorage, as well as the houses on the mission compounds, did not at first have toilets connected to septic tanks. At the Anchorage there was a narrow room to the right of the eating area that had four-legged stools with chamber pots resting in the seats. Used pots were kept covered and available ones uncovered. A door to the outside allowed a “lutchy,” always a woman as I remember, who was of the lowest of lowest in India’s caste system – an “untouchable” – to enter the room and clean out the pots’ contents every day. (Years later I told my friends at Concordia in Fort Wayne about lutchies and for a time I was called “Lutchy Lu” or just “Lutch.” My friend Ted Taykowski, on occasion, still uses it, just like I still call him a “dumb Polak”.)

In short order, Dad arranged with Mr. Malachi to have a room attached to where the outside door of the toilet area had been and in it installed a toilet connected to a new septic tank. The room also had a cement walled reservoir in it, fed with drawn well water that was poured through a tube from the outside, from which we drew water to hand-flush the toilet. However, the servants’ cacoose never changed. In the back quarter of the compound, it had four walls, a space for an entrance, and no roof. Inside were ten, or so, widely dispersed granite cubes upon which a person squatted, deposited, and from which the lutchy collected. Actually, many Indians, especially men, didn’t use a cacoose to urinate. It was a common sight, as we drove along a road, to see men squatting by the wayside, backs to us, relieving themselves.

If I had to use the toilet in the middle of the night, it wasn’t easy to do. Each room of the house on the first floor could be locked from the interior hall side with a bolt placed high on the doors. That was to prevent a burglar from taking off roof tiles and lowering himself into one of the side rooms, or into the back of the house, without having to repeat the process to get into another room. Dad became more security conscious after a thief stole Mom’s dentures from a windowsill and it took months to get them replaced. So, as a young lad who couldn’t reach too high, unbolting all the needed doors to get to the toilet made me, at times, grin and bear it.

Despite living in a house that was grander than most Indians lived in, we needed servants to help run the household. Sarganum was our cook for many years and one of his relatives, Pakianathan, was the gardener who tended the grounds and did other jobs outside of the house, such as drawing the well water. Also, in the first years of my life, until 1938, an ayah,” – a child caretaker – watched over us children until we went away to school. I have no idea what her name was. I simply called her “Ayah.” She slept in our house, while the other servants lived elsewhere in Nagercoil.

One of the basic reasons for needing servants was that there was no plumbing or electricity in the houses in my early years on the mission compound. There we used kerosene oil lamps. When we returned to India in 1939, The Anchorage, while it at first didn’t have plumbing, did have electricity; but just ceiling lights that could be used only at night because only then did the city provide an electric flow. With no wall sockets and no constant electricity, we didn’t have electric pumps, appliances, or other equipment. That translated into a way of life that was similar to rural America in years past, and it’s hard to imagine now. Our water was drawn from the well by the gardener, so it had to be sanitized to drink and for cooking. It was boiled and stored in long-necked, earthen-ware “goosah” jars, which sat on a rack in the pantry area. Bathing water also was drawn from the well and poured from the outside into another reservoir in the bathing area. To bathe I stood in a curbed area alongside the reservoir and used a pitcher to pour water on myself. There was no hot water. The used water then ran to the outside through a hole at one end of the curbed area.

Despite having no daytime electricity, Sarganum became a proficient cook under Mom’s tutelage, using a stove and oven made of brick and fueled with wood. We didn’t have a refrigerator and so almost daily he walked to the bazaar in downtown Nagercoil, where in open-air markets he purchased perishable foods for use that day. Sarganum also took care of the chickens, gathering eggs, and killing and dressing any fowl used for a meal. He also milked the water buffalo. The gardener would occasionally lead it to a nearby pool and bathe it.

With no washing machine, it was the “dhobi” – the laundryman – who regularly came to pick up our soiled clothing and linens. He loaded them on a donkey and took them to a river to wash them by hand, soaping them and whacking them on a smooth rock to get the dirt out. What the dhobi didn’t iron had to be pressed at our house with a charcoal heated iron. Also, our shoes were handmade. The shoemaker came to our house, traced the outline of our feet on a piece of paper, and then produced footwear that resembled a style that Mom showed him in a Sears catalogue. We each also had a pair of sandals.

In most respects, the days spent in Nagercoil were quite carefree. I had a roof over my head, food in my stomach, clothes on my body (especially a sun helmet on my head), and friends with whom to play. Dad and Mom didn’t put many restrictions on me; as long as they knew where I was going, I could do as I pleased. My best friends in Nagercoil were the Zorn boys, Bob, my age, and Ted, his younger brother by two years, who lived next door in God’s Grace, and also Norm Schroeder, who lived in a mission compound bungalow beyond the one in which we had lived when I was born. We all had bicycles and so we went back and forth, roaming about together.

We lived in the northern part of Nagercoil, our house facing east on the west side of the frontage street, which I called Water Tower Road. The tower to the north, a large reservoir set high on pillars, was at the crest of the street’s incline. A turn to the right out of our compound gate headed us south and gently downhill to the center of the city, two or more miles away. Most of Nagercoil’s main streets were constructed of small granite stones, packed together by a steamroller to make solid beds graded, except downtown, to ditches at each side.

Our street curved past the Maharani (Queen) of Travencore’s Nagercoil palace compound and on past the high school. (South India, already then, had a high literacy rate as the children in the city were well educated and many of them spoke excellent English, as did their parents.) Just north of the high school another street veered off to the left and proceeded into the center of Nagercoil. Our street continued south and ended at a T intersection, across from which was a Shell station, the only gas station I remember Dad using. Turning east on the cross street brought us to the center of the city where there was a circle street, from the hub of which arose a yellow water tower. It had a source of water that the families nearby daily visited to obtain their needed supply. Women, never men, each carried a large brass jug and filled it for their family needs in lieu of any piped in water to their homes.

A movie house, or “cinema” as the Indian’s called it, faced the downtown circle. In the 1940s, India had the largest movie-making industry in the world. Indian movies, at least at that time, retold religious sagas. They were long and tedious, had involved plots, and never depicted affection, especially not kissing. Probably, because of the poverty at that time, the movies were the “opiate of the Indian masses.” The playbill of the week was advertised throughout Nagercoil by a man who walked about the city with a drum slung in front of him so that he could beat both sides of it with lead-weighted fingers. He was accompanied by another person who distributed printed handouts of that week’s featured films. I still can utter the sounds of the drums that attracted attention: dicker-dicker-dum-dick, dum-dick, dum-dick, dicker-dicker-dum-dick, dum-dick, dum-dick. We, however, never went to Indian movies.

Next to the cinema was The Emporium, an upscale store that had a rather British snobbery about it. Dad and Mom would sometimes shop there, but the store that we really enjoyed was Tirichutambalum’s, east of the circle, where Mr. Tirichutambalum would greet us. I always thought he had more common items in his store, like candy and such, which I preferred over what The Emporium offered. None of the stores in Nagercoil had glass fronts. They were totally open to the outside and were then enclosed at night with tall wooden shutters placed the breadth of each storefront. The street that Tirichutambalum’s faced continued eastward to the city’s hospital, built and administered by the Salvation Army. As one left the downtown area of Nagercoil, heading east, rice fields and palm trees interrupted the flow of the city. Beyond them then, to the left, could be seen the cluster of red-roofed buildings that comprised the hospital. It had already served the Nagercoil area for years.

The Salvation Army doctor and surgeon in-charge’s name was Noble, an American, and one of the nurses, the only one whose name I remember, was Miss Lauttala, a native of Finland, and a friend of Mom’s. I was born at the hospital, but also, at the age of six, had my tonsils removed there by Dr. Noble. In the operating room, a gauze mask was put over my face and chloroform dripped on to it and I was told to count back from 100. I told them that I couldn’t breathe, but in a few seconds it didn’t matter. I stayed at the hospital at least three nights. Dad, being very practical, gave me a wallet (for what money, I don’t know) as a get-well gift. The next day Mom brought me a toy that had a little car that went down ramps and I wasn’t as bored as I had been. The hospital was especially fearful to me when I knew that I was to be inoculated for small pox. Dr. Noble scratched a dollar sized portion of the skin of my left arm just below the shoulder with a curette and put vaccine in the wound. Two scars are still visible on my left arm. And it also was at the hospital that we received dental care.

A room on the far right front of the main building was the torture chamber with its chair, along side of which was a dental drill driven by a treadle operated by the dentist. No anesthesia was administered before minor caries were drilled out for the cavities to be filled with silver. In later years, in my early twenties, a dentist in St. Louis reamed out many of my molars, leaving just sidewalls, and filled the chasms. In so doing, he saved most of teeth. Whether the poor quality of the dentistry in India necessitated that, or whether it was just too much candy, I really don’t know.

Leaving the hospital and heading back west through Nagercoil put us on the road to the ocean, where we enjoyed swimming either at Cape Comorin or at Muttum (rhymes with poot-tum). Cape Comorin – Kanya Kumari now – at the southernmost point of India is where the Bay of Bengal, the Indian Ocean, and the Arabian Sea meet, so that at the same time the sun can be seen setting in an ocean to the west and the full moon rising in another to the east. Cape Comorin didn’t have (and probably still doesn’t have) very good swimming beaches. So, whoever administered the area had a “swimming pool” built that was no more than a large concrete walled area that acted as a sheltered harbor, with an opening to the ocean which allowed seawater to enter it. A swimmer didn’t have to deal with the crashing waves, and yet the level of the pool constantly undulated according to the breakers on the outside. It was in that saltwater pool that I first swam.

Today Hindu faithful visit a temple at Cape Comorin dedicated to a virgin goddess. There is also a memorial built at the place where the ashes of Mahatma Gandhi, the man who achieved independence for India in 1947 from the British Raj, were kept before being immersed. On the 2nd of October, his birthday, the sun’s rays fall directly on the spot.

I especially enjoyed Muttam, a lovely beach on the shores of the Indian Ocean north of Cape Comorin. Muttam’s beach sloped gradually and I could frolic in the ocean surf. There was no heavy undertow where we swam, even though the breakers would be so high at times that I would be swept under the water, only to re-emerge and be propelled toward the shore. Going to the beach reminds me of a side story. Already in those days, as a nine year old, I avidly read TIME magazine. An article in it, reporting the ongoing events of World War II, quoted a song that referred to a portion of the military as “goddamn engineers.” On the way to the beach, sitting between Dad and Mom in the front seat of the car, I asked Dad what a “goddamn engineer” was. It was said in all innocence; I truly hadn’t heard such an expression before. In fact, I never heard profanity, cursing, vulgarity or God’s name taken in vain until I came back to the States in 1945. But even now I still remember Dad’s discomfort, though I don’t remember his answer.

And now more about daily activities in Nagercoil. The family arose early in the morning and ate breakfast, already prepared by Sarganum. If I didn’t have any floors to wash, I played with my friends until lunch. We had a few toy trucks that kept us happy, or we played board games, or explored on our bikes. A short-lived enterprise was the publication of a newspaper, of which copies of one issue (probably the only one, even though the first issue promised “This paper will be given once in three days.”) are in my files. It’s dated October 25, 1943, after I had just turned ten. The Silver Paper was typed sideways on an 8 and 1/2 x 11 sheet of paper, using carbons for extra copies. Its three columns have news items separated by lines. Bob Zorn and I are listed as editors, though I remember doing the typing on our upper veranda. The objectivity of this editor was lost on the very first news report at the upper left which states: “This morning some boys (Bobby, Ted, Dave, and I) made a village on the sand pile.” But there was an editorial office, made of suspended blankets, as another item farther down announces:

Mail Club

Bobby Z. made a little house on Zorn’s Veranda,

which we are calling The Silver Paper Meeting House.

- Where the staff met:

- The Silver Paper Club met this morning and Teddy Zorn was put in the club.

This club will be called S.P. M. H. (Silver Paper Meeting House.)

- And maintained it for the future:

- The S.P.M.H. made their headquarters look better.

They made the roof so it would not sag in, and covered up one side.

Now the S.P.M.H. now (sic) has pictuers (sic) in their house.

The S.P.M.H house roof blew off, but now is fixed by putting blocks on the side of the tent.

- There was a culinary section:

- Eat Mrs. Zorn’s icecream its (sic) the best!

Mrs. Strasen made cookies but they had lumps of soda in them.

We are sad to say that Mrs. Zorn’s yeast starter was no good.

- And obituaries:

- On Oct. 24, one chicken was executed. This chicken belonged to Strasens

- Aug. 23 Today 5 girls and 1 boy had temperature.

Aug. 27 Lois M. get (sic) yellow Jaundice and now is in bed on a diet of barley water. Lydia R. has it also. The children are having debates wheather (sic) it is contagious or not.

Death

Other reported items include taking care of the surviving chickens, the day’s weather, hearing an unsighted airplane the day before, noting that no airplanes “went over” the day of publication, and also that the Nagercoil missionaries went to a conference.

A similar paper in my files, The Bugle Call, also only one issue, published in August of a school year in Kodaikanal, lists John Bertram, Editor; Teddy Zorn, Asst. Editor; Luther Strasen, Printer; and Bobby Zorn, Asst. Printer. It reports the games we played at the boarding home and important items, such as:

The day continued at the The Anchorage with lunch at noon, followed always by a nap. Mom often said, “You don’t have to sleep, but you have to lie down for half an hour,” hoping that I would fall asleep. But I usually spent the time reading. It was the hottest time of the day and Mom and Dad would also nap. The later afternoon wasn’t much different than the mornings. We usually observed the English “tea time,” about four p.m., with a light snack. When Dad was finished with his work, he and Mom would often go walking, returning in time for supper, prepared and served by Sarganum around eight in the evening. Every meal began with the “Come, Lord Jesus” table prayer and we never left the table until we prayed Psalm 107:1 that begins “O give thanks unto the Lord.” Supper always concluded with a devotion time. The devotional booklet Portals of Prayer was used, as well as Egermeier’s Bible Story Book. Some evenings I was the reader of the Egermeier story. That book gave me a foundation in Bible history and by the age of ten I understood the Bible’s basic continuity and its human characters. In addition, Dad led us in reading select psalms, so that by my early teens I realized that without any effort I had memorized large portions of those psalms. That came in good stead later as I made pastoral calls, using comforting psalms without the need of a book. As a Nagercoil day came to an end, since electric lighting was from a ceiling bulb and not conducive for any lengthy reading, we retired to bed soon after darkness had enveloped our world.

At this point it should be understood that, even though our family didn’t have some modern conveniences, the missionary life was not one of great hardship. Mom supervised the household, but having servants allowed her a great deal of time for leisure activities like reading, taking afternoon naps and late afternoon walks. Dad did most of his work during the week in the mornings. He and Mom both enjoyed song and music, though Dad was the real singer, with a good bass voice, while Mom had a thin soprano range. Dad had a violin that he would play in his study on many afternoons. He also built his own flutes out of bamboo, drilling the holes and then using rolled up sandpaper to enlarge them to the correct circumference to produce the correct musical scale. Some days there would be an hour or two of repeated musical tones, as he blew and then sandpapered, blew and sandpapered again.

As Mom decided menus, she utilized the food resources in the area. We ate a great deal of rice, chicken, fish, and tropical fruits, such as plantain, papaya, pineapple, and guava. We had native vegetables, such as okra, and brinjahl (eggplant), and portalungi, a long gourd. We also enjoyed potatoes, carrots, onions, cabbage, and some lettuce. But they were grown farther north near Bangalore, from where we would occasionally receive a bushel basket of vegetables that had been especially ordered and contained those more European varieties. Beef was eaten less because the Hindus considered the cow sacred and the slaughtering had to be done by Muslims. We also ate mutton, which is a word for sheep meat, but I think it was goat, because I never saw a herd of sheep in India, but lots of goats. Maybe mutton was a euphemism used by Mom. Beef liver and brains were also served at times. Mom (whose cookies weren’t always soda infested) set the daily menus with Sarganum.

As I previously noted, we didn’t have a refrigerator. The Zorns, however, did have a kerosene-fueled one with a small freezer section. At times Mom prepared a custard mix and, using some space in the Zorn’s freezer, produced a kind of ice cream dessert. Dad built an icebox, a large chest with a lid on the top, lined with galvanized tin. He was able to buy block-ice at the Salvation Army hospital, but the box must not have been insulated enough to be worth the effort and he soon used it to store flour that was bought in a large quantity. I well remember the latter use because there were times that my job was to sift the flour to get rid of the grub-like worms and other matter that had taken up residence in the flour. As noted, because of the lack of refrigeration, Sarganum shopped almost daily in the market. Fish caught during the night was literally run in from the ocean every morning. Bearers trotted the more than ten miles to the Nagercoil fish stalls, each runner balancing a basket of fish on his head by grasping ropes hanging from each side of the basket to steady it. The un-refrigerated catch was then displayed amid a myriad of flies. The meat stalls were also open-air, the carcasses hanging on hooks, the portion of meat desired then cut to order (but not into the tempting steaks and other cuts as presented in today’s American meat markets.).

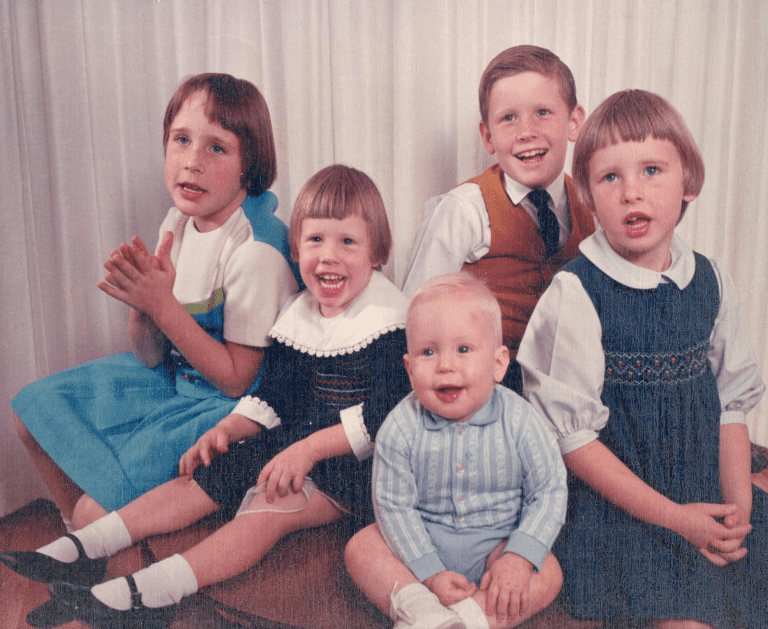

Breakfast often consisted of oatmeal porridge and fruit. I also enjoyed ahpums, made of rice flour and cooked to form a large, white kind of pancake on which I would smear butter and jelly. Dinner, as we called lunch, was a light meal, and the supper meal was the main meal. We grew up with the flavor of curry. Curry is a combination of spices, usually with a base of cumin and coriander, that is used to season vegetables, meat, or fish in a stew-like mixture served with rice. Most Indian households have a granite curry stone on which the spices of their taste-desires are crushed with a heavy granite rolling pin and mixed with water to form a thick curry paste. The paste is then rolled into a ball and used for flavoring in subsequent meals. The addition of chili peppers dictates the “heat.” As Sarganum, in the outside area between the kitchen and the bath, would crush and roll the spices on the stone, I would sit and talk with him about various things. Though curry is sometimes prepared with hot spices, it actually is more often blended to form subtle and delicious flavors – which Americans seldom savor. One of my favorite curry meals in India was made with huge shrimp (prawns) that had been caught the night before in the Indian Ocean. Along with curry, I’ve also always enjoyed chutneys – side condiments that add more flavors, just as Americans eat corn relish or pickles, or olives. Chutneys can be spice-hot or sweet, made from mangos, limes, lemons, and such. Arlene (my wife – who’ll come into my life story in due time) soon enjoyed curry and now cooks an excellent variety of it. But our children, when young, refused to try the curry food that we “former Indians” prepared. The children eventually also became devotees of curry (how or why I don’t know) and some cook it for their own families. However, curry wasn’t our only diet. For instance, Mom delighted me at times with “The Gravy Boat,” a wall of mashed potatoes encircling a platter, with beef and gravy inside the circle and slivers of toast stuck into the wall like flag poles. Mom would also have chicken and fish prepared, using American style recipes.

Sarganum did speak English, but I also learned and spoke some Tamil, the language spoken in our area, with him and other Indians. Actually, there are some dozen major languages in India along with some 300 dialects. Two of those languages were spoken in the state of Travencore, the governmental area at that time in which Nagercoil was at the southern end. Travencore, shaped like a cucumber, nestled at the extreme southwest bottom of the Indian peninsula. The longest concrete road in India at the time led north from Nagercoil for forty miles to the capital city, Trivandrum, where the Maharajah of Travencore lived in oriental splendor. He was a young, very handsome man who traced his position back for generations, but then existed as a figurehead by the grace of the British colonial authorities. A problem in Travencore, however, was that the people in our southern portion of the state spoke Tamil and in the northern half, starting just south of Trivandrum, the language was Malayalam, with no similarity between them. When India became independent in 1948, the matter was resolved by making the northern area the state of Kerala, where only Malayalam is spoken, and the lower Tamilian part was joined to a larger area to the northeast that today is the state of Tamil Nadu. English, however, continues to be the language that enables those who live among such diversity of tongues to have an understanding of one another. As for the Maharajah of Travencore, along with others of his position throughout India he was divested of any territorial rights when India gained its independence from Britain. If there are maharajahs today, they’re more tourist attractions than anything else.

I learned my Tamil from the ayah. My sisters knew a great deal of Tamil when they were small, but quickly took up English when they started school and forgot most of the Tamil. I don’t think that Dave or Ted learned much Tamil. My Tamil is mostly table and bazaar talk. Words and phrases like “bring,” “I want,” “yes,” “I like,” I know”(and their opposites), “how much,” “too much,” food names, and the Tamil names for the cutlery and dishes on the table. I speak the Tamil I do know without an accent, and when Indians hear my few sentences they assume that I can carry on a fluent conversation – which I can’t. By accompanying Dad to the village congregations for worship services, I also came to know, just by hearing them so often, some lines and tunes of a few Indian hymns, as well as parts of the liturgy. However, I still don’t know what most of them actually mean. Years after returning to the States, I rattled off a long sentence in Tamil to Dad, with no idea of its meaning in English, and then asked him what I was saying. He informed me that it was the First Article of The Apostles’ Creed.

I regularly accompanied Dad to the village congregations that he visited on Sundays. I never wanted to be anything but a pastor (though not necessarily a missionary) and thoroughly enjoyed going with him. During the year or so that I was the only child not yet in school at Kodaikanal, Mom also went with Dad and I would sit between them, often putting my four year old head on her lap and falling asleep as we drove along. When we returned to India in 1939, Dad had a Ford Model A at the Anchorage, which had the British right hand steering. It stood high, had running boards, and carried a spare tire outside on the back of the luggage compartment. It had no glass except for the windshield. There were side curtains which could be snapped in place in the event of a rainstorm, made of canvas with heavy, yellowish celluloid panes. Dad started the motor by using a crank at the front under the radiator. He set two levers at the steering wheel (I think they were for the spark and magneto) in a certain way. As he cranked, Mom, and later I, were ready, as he called out instructions, to change their positions once the motor started running.

In due time, I often was the only one who accompanied Dad to the villages. Early on a Sunday morning he drove north on the concrete road toward Trivandrum and then, after only a few miles, switched to side roads to reach the villages. Dad was assigned about seven village congregations and would usually visit one village a Sunday to celebrate Holy Communion there. While some of the sites had a native pastor, most of them had a catechist who had been trained, but was not yet ordained, who took care of the services and people in the meantime. On the route to the villages, some of the side roads were also made of granite that had been broken into small stones, while others were mud roads. The more used roads were often filled with bandy traffic. Bandies are two wheeled carts, each drawn by a yoke of oxen. They were, and in some areas still are, the “semis” of India, carrying loads to the cities and the villages, often traveling in long procession, their wheels cutting deeper and deeper ruts in the stone road. Dad, in the car he had before the 1938-39 furlough, honked a horn suspended on the corner of the windshield, manually squeezing a rubber ball to push the air that sounded the “pramp, pramp” alert to those whom he wanted to pass. The Model A had an electric button on the steering wheel that activated a horn with a harsh “garugah, garugah” sound. At some of the villages, with names like Varathalumpallum, Kartakardi, Enayum, and Nunchikordu, Dad drove right to the congregation’s place of worship. There were others beyond the reach of the road, so he parked the car and we walked the rest of the way. Sometimes the path was on long mounds that paralleled and separated the rice paddies and finally led to a village that was an island in the rice fields.

Two of the congregations each had a substantial building in which the worship service was conducted; with walls of stone, covered verandahs, framed windows, tile roofs, and floors and benches to sit on. During the week, elementary school was conducted in them. That’s why they also had a short piece of railroad tie that was struck with a hammer to signal students to re-gather or to announce the start of worship. However, most the villages had worship buildings, called “pahnduls,” that were more simply constructed. Sun dried bricks were used to erect walls about four feet high in a rectangular shape, with an opening at one end for an entrance way. Spaced every six feet or so into the walls were wooden upright supports about another four feet high. They held a pitched framed ceiling of wood that was thatched with palmyra (palm) branches. The fronds of each palm were woven together to form a long mat, and when enough mats were laid on top of each other they formed a watertight roof. The space between the wall and the ceiling was open to the elements. The dirt clay floor, which if left untreated would have been soft and dusty, was surfaced with cow manure to form a more stable and dust-free area. The fresh manure was smeared on the compacted dirt, let to dry, and then topped with more coatings. The resulting firm surface, without any odor, was swept when necessary and, when it eroded in places, was repaired with a quick patch.

The houses of the villagers, though much smaller, were of similar construction to the worship pahndul; usually just one room, with a dried manure floor, and a cooking area set up outside the front entrance. One of the duties of housewives of poor families was to collect the droppings of the cows that wandered about, for use as both flooring and to burn as fuel. The homes of these poorer people had hardly any furniture. They slept in their one-room houses on mats, again woven from palmyra fronds, which they rolled up during the day to make room for the family activities. When there are no chairs, Indians have a way of squatting, as they visit with each other or cook and eat their meals, to which they early become accustomed. My knees would have ached.

And so there also was little furniture in the worship chapels. Mats were rolled out for the worshippers to sit on cross-legged, though some chapels had basic backless benches for the adults. The altar was a table with a cross on it, along with the Communion elements. Dad had a chair and I, as the missionary’s son, was given a stool to sit on, also in the “chancel.” From my place I looked out on the congregation. “Tumbies” and “penpurlays” (little boys and girls) on the front mats, parents on mats or benches behind them, sang hymns with great fervor. Mothers nursed their babies during the service because they didn’t have milk bottles. Not much has changed to this day in the rural areas. These deeply religious Christians, who are a great minority in India, still come together to hear God’s gracious message of salvation through Jesus Christ and to receive His blessings in the sacraments.

A number of things about the dispensing of the sacraments remain in my memory. Indians often drink by never placing a cup to the lips, but pouring the water into the mouth and gulping it straight into the throat. So Dad wouldn’t touch the communion chalice to the communicants’ lips. Rather, he steadied their chins with one hand and with his other hand poured the wine from the chalice into their mouths. Also, because the poor couldn’t afford diapers, on a number of occasions during baptisms I saw a not so spiritual stream of water rise up from a baby that was about to be baptized.

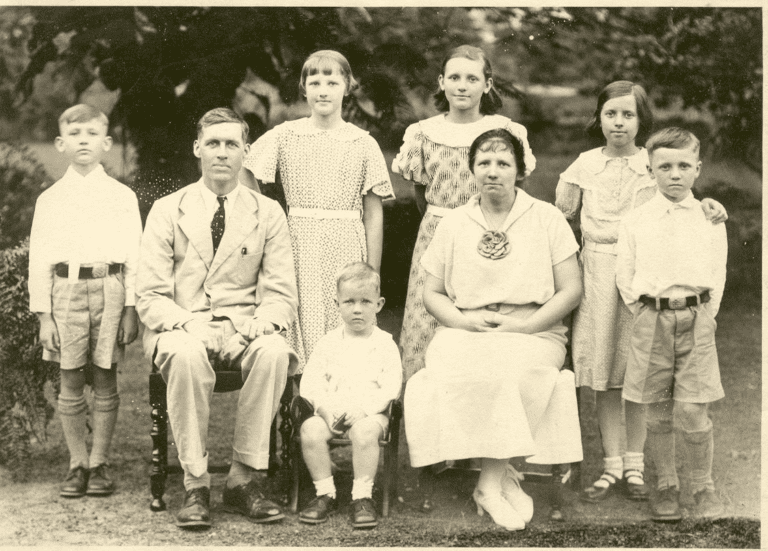

This picture was taken on April 21, 1938 at Varathalumpalam, one of the congregations with a stone building. It was the Sunday after Easter, and Dad and Mom and I had garlands made of flowers and fruit put about our necks, and many of the worshippers were dressed in their best. Sometimes after the services a special treat would be offered to the missionary and any of his family that was along. A man, probably one who made his livelihood by tapping palmyra trees for the juices from which “jagury” sugar is extracted, climbed up a nearby coconut tree. His arms were around the trunk and his feet were loosely encircled at the ankles with a cord loop made out of coconut fiber. The loop dug into the rough bark of the coconut tree, enabling him to stand on the trunk and then, holding around the trunk with his arms, he drew his legs up to the next position, again stood, and so on up to where he could harvest coconuts. On the ground again, he cut off enough husk to reveal the nuts, and opened them so we could drink the fresh liquid.

At other times, however, Dad had to meet with the village catechist and so I would go to the car and sit there by myself. Oftentimes, a circle of Indians, mostly children, would surround the car, just standing and looking at me. I was an oddity – I had white skin. Facial features of Indians are similar to Caucasians, except their skin is various shades of brown, sometimes almost black. Their hair is black. And there I was, with a white face and blond hair. I would say “Po!” to them, “Go away!” But they didn’t. Then Dad came and he drove us home. The next Sunday I would be with him again.