From My Mango Tree

by

Luther G. Strasen

(Updated in 2006)

The Auto-biography of Luther George Strasen

<>< <>< <><

Chapter Four – The Tree

Concordia, Fort Wayne, was chosen for Dave and me because of its proximity to the rest of the siblings. Polly had started her first year of teaching at the Detroit Institute for the Deaf. Ruth was still attending school at Valparaiso University and Betty was still working as a waitress in Chicago, waiting to marry Fred Nohl when he would graduate from CTC. Ted had joined the U. S. Navy and was sent to school, first at Central Michigan College in Mount Pleasant, Michigan, and then another semester at Valparaiso. The navy didn’t need him at that point and released him. He spent a few years in the Chicago area and then joined the U. S. Army and served in Korea. Dad and Mom financially supported Dave and me. They set aside $50 a month for each of us to pay for our room and board, which was $360 a year per student, and other incidentals. Where that money came from, with Dad’s meager salary, I don’t know. The Mission Board might have helped missionary families with their children’s schooling.

The campus of Concordia, Fort Wayne, was sixteen blocks due east of the downtown, between Maumee Avenue and Washington Street, with Anthony Boulevard as its eastern border. It’s the present site of Indiana Institute of Technology (which has razed all of the buildings except for the oldest, the former administration building). The buildings were erected, starting in the last half of the 19th century, for boys and men, from high school freshman through college sophomores, studying to be Lutheran pastors. However, the Fort Wayne Missouri Synod congregations had started a regular coeducational high school in the 1930s, and that school was also using the classroom and athletic facilities. The campus consisted of two large classroom buildings, one of which had a large chapel and the library on its second floor. There were also the administration building, two residential dormitories, a dining hall, gymnasium, and a football and track field. All the buildings were served by one power plant. Professors’ homes lined a U-shaped street that had its entrances on Maumee Avenue. Most of the dormitory occupants were pre-ministerial students, who came from Indiana and the states surrounding it; though some, like Dave, were regular high school students. Though the ministerial high school and the regular high school had separate faculties, the sports and social activities of both high schools were combined. In addition, a junior ROTC, which had been on the campus for years, was mandatory for all of the male students from both schools. Its officers, during my freshman year, were the men in the college. It was from that battalion that Concordia Lutheran High School’s sports teams, still to this day, are named Cadets.

Mother also saved my letters that I wrote during my high school days, most of them addressed to Vallioor, India. More than 50 years later I finally also read them. Sometimes Dave added a few sentences, and some of the letters have paragraphs by my three sisters, written on those rare occasions when we got together. In a letter sent in my first weeks at school to Dad and Mom, still in New Germany, I made a request. “As you know,” I wrote, “in 5 more days I will have been in the world 13 years, being born in the year of our Lord 1933 (right?). Well, please send me a whole cake, enough for six persons. Because that night we are going to have (our room) a chuck fest and I promised a cake so just make one and crate it and send it so it arrives by Saturday (no delivery or mail on Sunday.) You know, send it like you sent to the girls and please mark it ‘DO NOT CRUSH.’ Make it chocolate. I hope this won’t be too much trouble. The rest I leave to you. P.S. There are five in our room, the sixth piece of cake is for David.” To further explain; in those days parents often sent cookies and cakes through the mail to their children away at school. “Chuckfests” were late night eating sprees, when the room pooled money to buy bread, Velveeta cheese, and Spam for sandwiches toasted on electric double hotplates (somebody had one), along with Pepsis. We could always smell when a room was having a chuckfest. I remember that the cake arrived. But in five days?

Most of the dormitory “rooms” consisted of a study room and a bedroom, and in my first year I lived with four other students. I was immediately introduced to the “juxtie system,” a discipline based on classes, which had been around for many years. Juxtie was pronounced “jookstee.” I’m sure that my dad had some form of it when he attended Concordia, St. Paul, Minnesota. It followed the German “gymnasium” – pronounced “gimnahzioom” – a secondary school system in that country in preparation for the university. The classes were numbered in Latin, six up to one: Sexta – high school freshmen; Quinta – sophomore; Quarta – junior; Tertsia – senior; Secunda – first year in college; and Prima, second year in college. So, as I started out, I was a sextaner. But more than that, I was a “juxtie.” Along with quintaners, and quartaners (in just their first few months of their year), we all had to answer at any time and place to any primaner or secundaner who yelled “Juxtie boy!” And then obey his commands. Those college upperclassmen had “shagging rights” and we had to do their bidding. The quartaners had to endure about six weeks of special harassment until they were given a “sendoff” that released them from being juxties. They, then, and the tertsianers, couldn’t wait until they became upperclassmen. Each dormitory room consisted of a mixture of the classes, with the upperclassman of each room being the “room deck” – the man in charge of that room, who saw to it that the juxties in his room kept it clean.

The system was reinforced with “haul-ups” that were designed through the years to enable the upperclassmen to intimidate and punish the juxties. They took place in a bathroom and toilet area known as a “locus” – Latin for “place.” At the center of each of the three floors of the two identical dormitories there was a locus. It was a large rectangular room entered by two doors, one on each side of its middle. It was divided into shower stalls at one end, toilet stalls and urinals on both sides at the other window end, and washbasins down the middle of the window end. Late some planned night, the upperclassmen of a dormitory turned on the showers in the second floor locus to steam up that end of the room. Then, after most of us juxties were already sleeping, they came to our rooms, jarred us into alertness and herded us into the area surrounded by the showers. They faced us, some standing above us on the washbasins, and spelled out their grievances, such as our not responding quickly enough to their juxtie calls, disrespect, or outright disobedience. There always were a number of juxties who had sinned greatly and they were put in the “hit parade.” Each was ordered to bend over and face into a toilet stall and hold his testicles (to preserve them from being damaged) and an upperclassman would thrash his bottom with the fiber end of a broom. Called “broom swats,” they were much more than a swat and, delivered with force, truly hurt. Other broom swats were also administered at any time or place when an upper-classman desired to punish. Fortunately, I received few of them. Most of the upperclassmen were sensible people, though a few did abuse the system. Even we juxties had to laugh among ourselves about some of them.

There was a short, baby-faced secundaner who would yell for juxties. Standing by his much bigger classmate friend, he would threaten the assembled juxties with something, but then look up at his buddy and say, “Won’t we, Bill!” However, the entire system was dismantled following my freshman year. The new president of the ministerial school, Dr. Herbert Bredemeier, a graduate of the system, simply put the upperclassmen in a dormitory by themselves and limited the ROTC to the high school male students. Even with the juxtie system, the dormitory life lead to a great bonding of the students, and a number of us still meet annually more than fifty years later.

My pre-ministerial curriculum was very much like Dad’s was years before, with the mandatory Latin, German, and Greek in high school. But for some reason, probably my immaturity, I simply didn’t study – and a language can’t be learned if there is no memorization of noun forms, verb conjugations, and vocabulary. So I failed freshman first-year Latin, and then sophomore first-year German. But I did start to study more in my sophomore year. My letters to India reflect my parents’ concern and are replete with my promises that I would study harder and get better grades. I still did badly with languages in my junior year, just passing, and I must have been scolded in a letter, with the threat of Polly paying me a visit. I replied: “I realize I’m still quite the unexperienced (sic) guy and I do have a lot of shortcomings. But I hope someday somebody would realize that I can carry some responsibility. I don’t think that Polly would have to come down to Ft. Wayne, for she knows practically all she could find out, right now.”

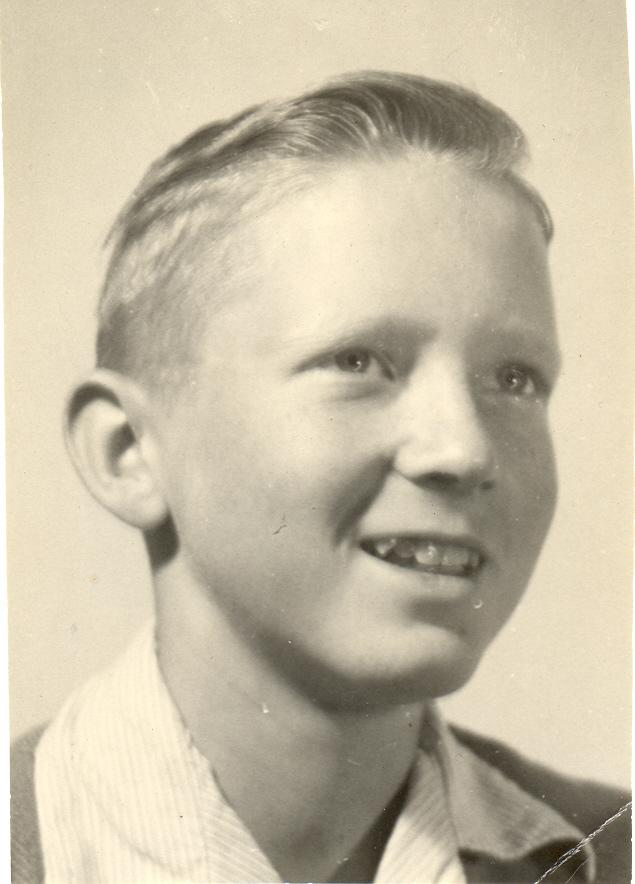

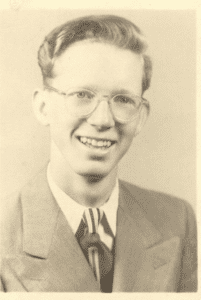

But the consequence of those academic failures was that I didn’t actually graduate from high school in 1950. I didn’t even attend my classmates’ graduation ceremony, though I did have this senior class picture taken for the school yearbook. During my freshman college year I took missed high school courses that I had to drop to get in the required Latin and German that I was behind. I could do that because the ministerial high school and junior college was just one continuous system with the same faculty. I then stayed at Fort Wayne for an extra college year, taking just a few courses that were necessary for me to graduate from Junior College.

So I fell a year behind the men I had started out with and I entered the ministry a year after them. During my college years, I worked part-time as a shoe salesman at Hutner’s Paris, a women’s department store, and I was able to work more hours that extra year because I had so few courses. It was during that last year at Fort Wayne that I became closer friends with three men with whom I had started out in high school: Ted Taykowski, who had gone to Valparaiso University for one year and had returned to Fort Wayne, dropping back to my year; Roland Barkow, who had attended Wayne University in Detroit for two years and had also returned, but now was one year behind me; and Luther Dau, who had started high school a year after me, and in whose class I now was. The extra year at Fort Wayne turned out to my benefit, as it gave me another year of maturity before I entered the ministry. Even more, it enabled me to be assigned to St. Martin Lutheran Church in Clintonville, Wisconsin, for my seminary vicarage. (I’ll explain further on what a vicar and his vicarage year are in the Missouri Synod, but suffice it to note right now that it’s an important practical year in a seminarian’s life.) St. Martin had a history of utilizing vicars, but didn’t ask for a vicar from the 1955-56 seminary class, in which I would have been if I hadn’t fallen behind. So I then would have vicared elsewhere, and today I wouldn’t have the foggiest as to the whereabouts of Clintonville, Wisconsin. However, after skipping one year, St. Martin again requested a vicar for 1956-57, and I was appointed to go there, and that was the beginning of a ministry during which I experienced and achieved far more than many of my peers did.

But now back again to Concordia, Fort Wayne. As the dormitories were closed each summer, I had to find a place to stay for those months. It was during the summer following my high school freshman year that I started to smoke cigarettes in order to show off (why else?). The rule at school, which was ignored, prohibited smoking below the junior year. Just a few months before, I had written to Dad and Mom about spending the summer of 1947 at a fellow student’s home and I reported: “Well, the boy is supposed to drink a bit and smoke. I do not like beer (it was thus underlined) and I will not start smoking. Maybe even I can make the guy quit drinking – maybe.” Instead of going to the boy’s home, someone arranged that I could spend the summer at Concordia Teacher’s College in River Forest, along with Norman Schroeder, who had just finished his freshman year there and whose parents were also back in India. During the day we cleaned the dormitories for summer school students and were on the loose the rest of the time. Ted was also in the area and I asked my brother for a cigarette, a Lucky Strike, and he said he would give me one if I would inhale. The next weeks were spent in a great deal of wooziness, but I was going to be a smoker! I didn’t tell Dad and Mom that I smoked, but in 1949 I inadvertently sent a picture of myself with a cigarette in my hand. They asked the question and I wrote back: “As for my smoking, yes I do. I’m not smoking much anymore and I hope to quit soon because I want to be in good condition for track next year. I guess the reason I started smoking was because the rest of my class does it, or most of them, and I just followed along.” As for beer, in another letter in January of 1949, trying to joke about it, I wrote: “I did accomplish one thing over (Christmas) vacation, though. I nurtured my taste for beer. Of course, Dad, you know your son, when he’s a minister, must be able to drink beer with the rest of his fellow ministers so – what I mean is that I never used to like beer, but I had some over vacation and I’m beginning, or I do, like it now. That’s not much to brag about, though.” I did stop smoking in October of 1961, fourteen years later. I had been to a pastors’ conference in Green Bay, Wisconsin, and, while there, smoked a great deal. As I inhaled another cigarette on the way home, I didn’t feel good and, snapping that cigarette out of the window, decided to stop. My resolve stuck. Cold turkey! In the next few months I gained 25 needed pounds.

Even during high school I did stop smoking for short periods. I always enjoyed sports, but I never had played basketball or football in India. While I was in high school, I played intramural basketball (at 6 feet tall, I played center – imagine that!) and, at 150 pounds, I wasn’t football material. Instead, I run track on Concordia’s team. Yes, I stopped smoking during the track season – and started again the day it ended. I ran the 100 and 220-yard dashes and the 880-yard relay in my junior year and showed potential. At the start of my senior year, my coach, John Hanak, introduced me to the low hurdles – and I took off. At meets, I ran the 100, the low hurdles, and the relay. I won all my races against teams in the surrounding cities, e.g., Columbia City, Auburn. In Fort Wayne, I was up against the national low hurdle champion, Archie Adams from North Side, and the state high hurdle champion, Sam Sims from Central High School. But in one race I tied Sims in a low hurdle race. I finished the season with 51 points, high for the track team. Ted Taykowski, a quarter- miler, was next with 29. But enough chest-pounding! Another extra-curricular activity I engaged in during my junior year of high school was the Snap Squad, a precision drill team that displayed its moves at basketball games and at the annual military tournament that the battalion conducted at the end of each school term. It was an elite group of about eight cadets and one had to try out for it. I was expected to continue participation in my senior year, but I declined – why I’m not sure. Maybe I didn’t want to spend the time needed for practice. Our son, Tim, while he was at CLHS, was also a member of the Snap Squad.

And I also taught Sunday school at Westfield Village. Rev. Paul Amt was the Lutheran “city missionary” in Fort Wayne and conducted services in a temporary housing development on the west side of Fort Wayne that had been quickly erected during World War II. Today the houses are gone and the site is a park along Catalpa Street. In those days, there was also a community building, where the Sunday school classes and a worship service were held for a racially mixed group. As I read my letters to India, I was quite gratified when I read a paragraph I wrote about racial prejudice in a 1949 letter, when I was sixteen. I again remembered how one of our daughters once told me I was racially prejudiced because I was concerned about her staying overnight with a black classmate in Fort Wayne’s black neighborhood. I told her that if I was prejudiced, she could be sure she would have been, because prejudice is taught and caught. While highly opinionated, my 1949 letter is a forerunner of my present stance. Back then I told Dad and Mom that I had seen the movie about racial prejudice, “Home of The Brave,” and it was a “wonderful movie.” “Talking about racial prejudice,” I continued, “Rev. Amt is leaving for Washington D.C. He took the call after the obstinate Ft. Wayne churches wouldn’t see things the right way. Out at Westfield it is a church for colored and white. Now the crazy churches around here want to start a separate “Jim Crow” church. Westfield has gotten along wonderfully and there has been no friction. Now they want to ruin everything by starting this church just for the colored. It disgusts me! I’d like to tell a couple of Lutheran pastors around here to look in the Bible and read the parts where we are told we are all of one faith. What difference does it make that a person’s skin is a different color? That’s another thing. Most of the churches around here won’t even let Negroes come into the church services. Oh well, a lot of people are blockheads. (Maybe I’ve let off enough steam and should change to a different subject.)”

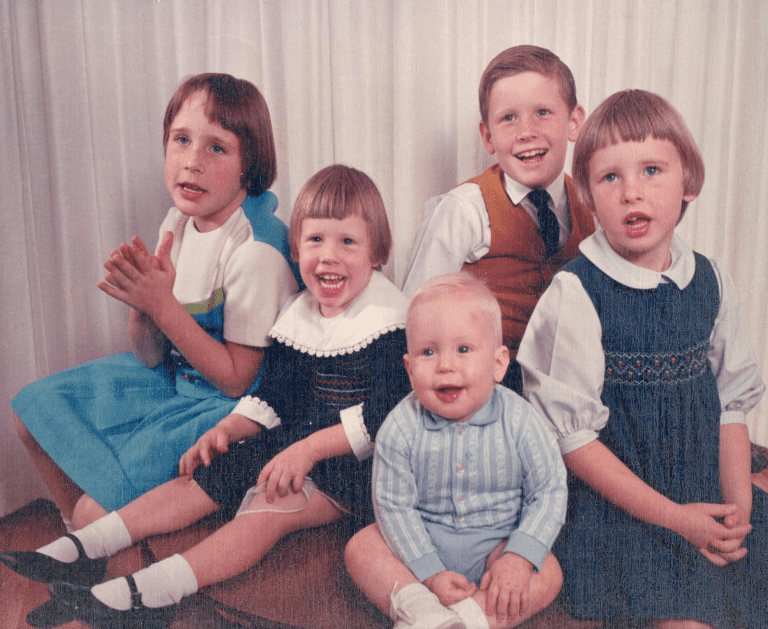

Most of my siblings became married during my high school years. Pauline married Charles Fenton, a civil engineer from Detroit, in 1949. Four sons, David, Charles, James, and Gary, were born to them and they lived in the Detroit area, where she became the principal of the Detroit Deaf Institute. During retirement, they moved to Port Huron, Michigan, where Charlie died in 1995. Polly died in 2000. Ruth married Roy Newquist, a writer, in 1949. They were blessed with three children, Karen, Karl, and Greta, and lived in the Minneapolis and Seattle areas, and then settled in Park Forest, Illinois. They were divorced in the 70s and Roy died in Los Angeles in 1997. Ruth took care of her children, while becoming a successful Prudential Life Insurance salesperson. She now lives in Chicago. Elisabeth married Frederick Nohl, a parochial school teacher, in 1948. They lived in Kankakee, Illinois, where he was principal of St. Paul’s Lutheran School, then for a year in Forest Park, Illinois, and finally in St. Louis, where he worked for the Missouri Synod’s Board of Christian Education. Their five children are Christine, Lisa, Constance, Paul, and James. They were divorced more than 20 years ago, and he died in 2000 in Zimbabwe, Africa, where he had gone to teach. Betty reared their children and later worked at a hospital in St. Louis. She married Robert Long, a widower, in 1996. Theodore married Dorothy Manichiello in 1949 in Haverhill, Massachusetts, near Boston, as he was ending up his army stint. He learned the shoe-making trade and through the years was a designer, pattern maker, etc., and knew the trade so well that he became a consultant and lived in places such as Puerto Rico and Mexico. Ted and Dot were blessed with three children, Eric, Kurt, and Lisa, and they now live in Auburn, Maine. David took schooling at Valparaiso University and was married to Annette LaFosse in 1954. Four children were born to them, Steven, Allen, Cherie, and Warren. Their family moved to Seattle and Dave became expert in computers. But the marriage didn’t last; Annette, who is now deceased, moved to California and Dave reared the children. There was another marriage, but it also ended. Dave died in 1991, but in the last days of his life married Prudence Worley, who had been his companion for some time. We six children produced 24 grandchildren for Bernhard and Henriette Strasen

As I’ve already mentioned, during the summers in my years at Concordia, Fort Wayne, I had to find a place to stay, because the dormitories were closed. After the summer of 1947 at Concordia, River Forest, my sister Polly arranged for me to stay at the Detroit Deaf Institute the next summer, where she taught and lived throughout the year. After Betty’s marriage on Thanksgiving Day, 1948, she and Fred had me in their home for some of the next summers. Fred was away at summer school most of the time and so I also helped Betty with the babies that were born in those years. One summer I worked as a soda jerk at the Kankakee Walgreen Drug Store. Mom and Dad came back from India in 1951, and Dad accepted the call of a congregation in Wartburg, Illinois, a small settlement a few miles from Waterloo, Illinois. But I didn’t summer with them and, instead, worked for a six-week period each of two summers on farms near DeKalb, Illinois, for the parent company of Del Monte food brands. Peas were grown on farms, and the first summer I pitched pea vines all day and into the night into viners that separated the peas from the pods. Long hours were necessary, because the peas were planted to be harvested at precise times for freshness, and immediately canned at a nearby factory. Each day’s work lasted as long as it took to harvest the designated fields. Pitching peas and cleaning the equipment was exhausting work, but it also paid well, enough to take care of much of my next year’s school expenses. The second summer in the fields I lucked into a tractor-driving job and hauled the peas from the fields for others to pitch. Much less tiring! I labored for a cement contractor the summer of 1953 (also for him in the summer months of 1957, after Arlene and I were married) and, during the summer of 1954, I was a counselor at Camp Lutherhaven in northern Indiana.

That Dad and Mom were concerned about not being with us during many years of our lives to give us closer direction becomes obvious in a letter I wrote in December of 1948. A few of my letters before that one already ask when they expected to return to the States. So, feeling badly, they must have considered that Mom should return early and leave Dad to finish the term in India. I responded: “About Mother coming over: I believe that it isn’t necessary for Mother to come over. We’ve (probably I was including Dave) taken care of ourselves for a year going on two years now and I think we can keep doing it. We have our brothers and sisters to see and I don’t think we need you as much as Dad does. Because he needs someone beside him to share his life, just like everyone else does. And, Mom, you’re the best one to do that. So why don’t you and Dad stay over there and we’ll see both of you in a couple of years anyway.”

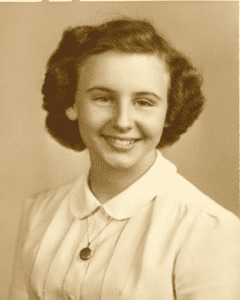

I first saw Arlene Lytal, now my wife of almost 49 years, in 1950 as she came into a morning chapel service when I was in my senior year of high school. She was a freshman at Concordia Lutheran High School, the coeducational part of the school. I had already dated in my junior year of high school. In those days couples “went steady” and I had a number of such relationships that lasted into the fall of 1949. The latest one had ended and I was looking for another girl friend. Arlene caught my eye. She was very attractive, well groomed, and had a lovely smile, her confirmation picture being a confirmation of that. I asked her for a date to a school social and, on February 14, 1950, I took the bus to Taylor and Brooklyn Avenue, walked the two blocks to 2131 Brooklyn, met her parents, and then escorted her to the Valentine’s Day “mixer” that was in the school gymnasium.

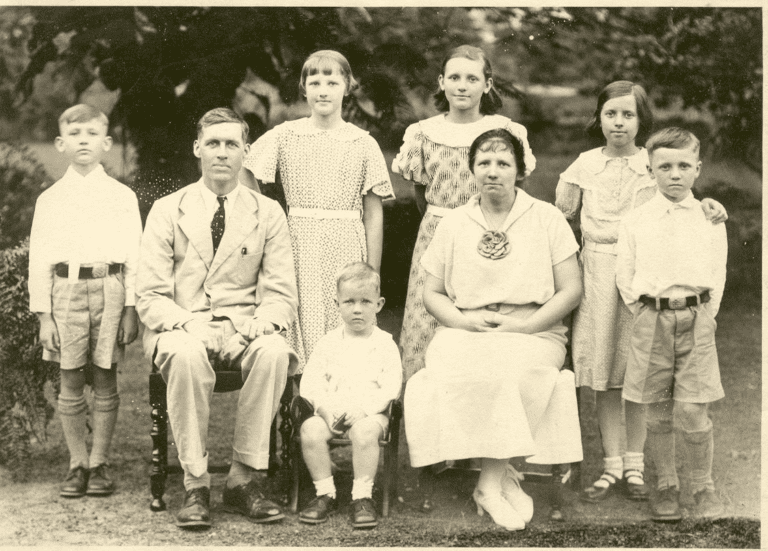

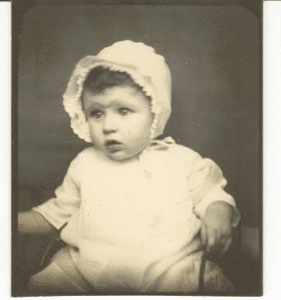

Arlene’s parents are Arthur Dale Lytal (who legally changed his name to Dale Arthur) and Hilda Laura Minnie nee Eisberg. Dale Lytal was born on September 27, 1907. His parents, pictured here, were Isaac Lytal, born in Canton, Ohio, on February 27, 1861, and Elnora Elizabeth nee Ritchhart, born on December 25, 1872, in Pierceton, Indiana. Elnora’s parents, both born north of Sidney in Whitley County, Indiana, were Ira Ritchhart, born about 1835, and Margaret nee Keys, born about 1839. Isaac’s youth was spent in Ohio and he worked at a tile factory in Edgerton, Ohio. He then moved with his family to Kosciusko County, Indiana, and there met Elnora, whom he married in 1896. Their first two children, Blanche and Ruth, were born in Etna Green, Indiana, and, later, Everett and Arthur Dale in Burr Oak, Indiana., and Earl in Hibbard, Indiana. The family moved to Fort Wayne in 1928. Dale and Earl, as young men, worked at General Electric in Fort Wayne. Isaac died on November 11, 1947, and Elnora on October 2, 1956. Isaac is buried in Greenlawn Memorial Park in Fort Wayne on the east side of Section 14, which is called Sunset Terrace. Elnora, however, is buried in Covington Memorial Gardens, a cemetery developed after Greenlawn Park, about two miles west of it on Covington Road. For some reason, their daughter, Blanche Greenick, had her buried in the Greenick family plot that she and her husband had purchased in the Garden of The Sermon on The Mount in Covington Gardens. Neither Isaac nor Eleanor’s grave has a marker. Besides the Greenicks, the Covington Garden plot also contains Arlene’s father, Dale, (unmarked) and Blanche’s sister Mary Lytal Theurer.

Isaac’s parents were Benjamin Lytal, born in Canton, Ohio, in 1822, and Susannah nee Shively, born on May 20, 1826. Documents in the possession of Wayne Lytal, Arlene Strasen’s cousin, reveal somewhat more. A letter, written on August 22, 1855, by Christly and Sarah M. Shively, to other brothers and sisters, tells of the death of their mother the previous day, describes her illness, and also states that their father is not feeling well. It asks them to visit, if possible. The daughters’ names, both in the same penmanship, are at the right hand bottom of the page and Benjamin Lytal and Susannah Shively’s names are in the same handwriting at the lower left hand corner. Whether they were all together, or the letter was written to the latter, is hard to say. Then, a deed, dated August 29, 1857, records the sale to Benjamin Lytal of Lots 4 & 5 in Myers addition in Williamstown, Hancock County, Ohio for $100. The family’s move to Kosciusko County, Indiana, is evidenced by another deed contracted by Benjamin Lytal. It’s dated May 23, 1879, for the purchase of the east half of the southwest quarter of the northeast quarter of Section No. 10 in Township 33, north of range No. 4, east in Kosciusko County, Indiana, and, as recorded at the bottom of the page, was released – paid for- by August 28, 1885. That land is now farmland that lies northeast of County Roads 1050 W and 650 N in Kosciusko County. Another deed, drawn up for Benjamin Lytal, dated February 1, 1879, is for the purchase of Lot 49, thirty feet by eight feet, for five dollars in Stoney Point Cemetery, Kosciusko County. Benjamin Lytal died in Kosciusko County in 1896. Susannah died there on August 30, 1877. Stoney Pointe Cemetery is reached by heading west on U.S. 30 out of Warsaw, Indiana, to County Road 700 W., taking it north to a T corner at 650 N, then turning west to the cemetery, about a quarter mile on the left. A chapel is at the left side of the main entrance and the gravesite is 50 or so feet behind the chapel, two rows in from the road. There are three markers, the largest for Susanna, designated as Benjamin Lytal’s wife. But there is no marker for Benjamin, and the other two stones mark Lytals unknown to my research.

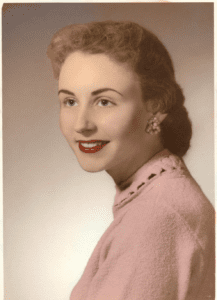

Hilda’s father, William Eisberg, was born in Hanover, Germany, on October 1, 1875, a child of Ferdinand Eisberg and Caroline, nee Bodeker. Hilda’s mother, Josephine nee Vine, was born in Sandusky, Ohio, on December 28, 1884. Both are pictured here. Josephine’s parents were Joseph Vine, who was born on July 25, 1833, in Germany and Laura nee May. Laura was born on September 7, 1843. Some say she was born in Scotland, but her death records state that she was born in Maysville (also spelt Mayville), Ohio. However, present day Ohio maps have no city with either of those names. She and Joseph were married in 1866 in Fairfield, Michigan, and he died in Fremont, Ohio, on September 2, 1902. Laura then brought the family, which included Josephine, to Fort Wayne, where she died on October 28, 1919. Laura Vine is buried in an unmarked grave in the middle of Section Q of Lindenwood Cemetery in Fort Wayne.

William Eisberg met Josephine Vine in Fort Wayne at the Bass estate, now the site of St. Francis University, where he was the coachman and she the cook. He drove the Bass’ carriage to fancy parties, wearing a top hat and formal coat, waiting outside until the festivities were over. John Bass owned and operated the Bass Foundry, then situated on the grounds of the present Fort Wayne main post office on Clinton Street. Their mansion is now the showpiece of St. Francis University. William and Josephine were married in 1904 and they had four children, William, Marie, Hilda, and John. For a time they lived on Spring Street, in a home near, or on, the Bass estate. Hilda, Arlene’s mother, recounted that as a child she played with the Bass grandchildren. They strapped metal spoons to their shoes and “ice-skated” in the third floor ballroom of the Bass mansion. She also remembers her father walking to Christmas Eve services at Emmanuel Lutheran Church on Jefferson Avenue with her on his shoulders. William and Josephine later purchased a farm at 3202 Flaugh Road, northeast of Fort Wayne. The farm is about a mile south of Bethlehem Suburban Lutheran Church and they joined that congregation. Arlene spent weeks at a time on the farm. It was there, when she was almost three years old, that she fell on some farm equipment and severely cut her left cheek. It became gangrenous and the therapy was to pour iodine into the wound. Josephine’s sisters had a prayer meeting for Arlene. The wound healed, but when I met Arlene she had an evident scar, that now has virtually disappeared. The Eisberg’s son, John, and his new bride, Louella nee Springer, lived with the parents on the Flaugh property and then purchased a farm in 1951, south of Fort Wayne on the Yoder Road. His parents moved with them and Josephine died on April 8, 1952, and William on October 12, 1953. They are buried in the St. Mark Lutheran Church Cemetery on Thiele Road, south of Fort Wayne.

William and Josephine Eisberg’s daughter, Hilda, born on October 15, 1910, attended the elementary school at Bethlehem Suburban Lutheran Church. She didn’t attend high school, but eventually, in the late 1920s, started to work at the General Electric factory on Broadway Avenue in Fort Wayne. While working at General Electric she met Dale Lytal. His brother Earl about that time married Hilda’s cousin, Emma Busse. (Emma was the daughter of Marie Busse nee Eisberg, the sister of William Eisberg, Hilda’s father.) The brothers and cousins all worked at General Electric and so knew one another.

Dale and Hilda (as pictured) were married on May 4, 1929. They had two children, Arlene Ann (pictured), born on November 22, 1934, and James Dale, born on October 3, 1940. Jim married Judy Conrad in 1962 and their two children are Edward and Susan. Ed is married to Cathy nee Nussbaum and has two children, the second with Cathy. Susan is married to Eric Grundke and they have two children. Dale and Hilda’s first home was 922 Goshen Road, near the intersection in Fort Wayne that is still called Five Points, where Goshen Road,

Sherman Boulevard, and Lillian Avenue meet. Now it’s an office for a used car lot. In 1940, the family moved to 2131 Brooklyn Avenue. During World War II, Dale served in the Merchant Marines for a short stint in the Chesapeake Bay area. He later worked at Joslyn Steel and finally was employed by the Fort Wayne City Utilities. Dale and Hilda had a troubled marriage and they divorced in 1951. Hilda was employed by General Electric all of her working days and retired in 1975. More about her will be interwoven through the next pages. Dale died on November 14, 1956, of a heart attack, suffered in front of 2116 Calhoun Street. He’s buried in Covington Memorial Gardens in the Greenick plot. These then are the roots that produced the wife of the sprout Luther:

Benjamin Lytal / Susan Shiveley

Ferdinand Eisberg/Caroline Bodeker

Joseph Vine/Laura May

Isaac Lytal/Elnora Ritchhart

William Eisberg/Josephine Vine

Dale Lytal/ Hilda Eisberg

Arlene Ann Lytal

James Dale Lytal

Arlene and I started to see each other regularly in 1950 and started to “go steady,” wearing each other’s class ring; mine on her finger and hers on a chain around my neck. I was a guest in her home almost every Sunday for supper. The small bungalow house had a porch, with a front door on the right into a living room; next was the dining room, and then the kitchen with a back door. The left side of the house had a short hall off the dining room, in which were doors to a bathroom in the center and a bedroom at the front and another at the rear. A stairs in the kitchen led down to a rather dank basement.

Arlene’s mother wooed me by cooking what’s still the best fried-chicken ever. Using lard was her secret, Arlene now tells me. We sat at the dining room table after supper and listened for at least two hours to the popular half-hour Sunday evening national radio shows, such as “The Jack Benny Show,” “Our Miss Brooks,” “Allen’s Alley,” and “The Red Skelton Show.” Television wasn’t being broadcast yet in Fort Wayne (not until 1952) and millions across America enjoyed the shows every Sunday evening.

In the fall of 1952, I disrupted Arlene’s and my relationship. I “broke up” with her, because I reasoned that marriage was at least six years away, too long to maintain the relationship. It was arbitrary on my part and she didn’t want it to happen, but I persisted. Though we didn’t date any more, she at least would speak to me when I saw her or called her on the phone. She still was in my thoughts. In 1953, during the spring, and then the summer when I worked as a laborer for a cement contractor in Fort Wayne, I took up with two other women, though not at the same time. The first broke off our relationship that June because her former boy friend came back from the air force. I then came to know the second woman. I was very enamored with the first woman; the second one was a “rebound” from the first.

Realizing that, in my first months after I entered Concordia Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri, I quickly broke off the relationship. At the same time, I also knew full well that Arlene had much more about her than those two women, because of her Christian faith, her pleasing personality, and her calm and sensible approach to life. I had never really stopped caring for her. That August she had started studies to be a nurse at the Lutheran Hospital School of Nursing in Fort Wayne. I wrote to her in October, asking for a date at Concordia High School and College’s homecoming weekend in November. She had all the reason and right to say no, but did accept. In retrospect, I thank God that she did, because the previous two women would not have enhanced parsonage life.

During the next months, while I couldn’t afford an engagement ring, I asked Arlene to marry me and she accepted. This is her engagement photograph, when it was finally announced. We spent the next years, she in Fort Wayne and I in St. Louis, continuing with our schooling and planning when to marry. During each school year I made trips to Fort Wayne to see her. We also spent time together during holidays and the summers at her home, or sometimes in Wartburg with my parents, or in Kankakee with Betty and Fred, or in Detroit with Polly and Charlie, and again later with Betty and Fred when they moved to St. Louis.

After graduating from Concordia Junior College in Fort Wayne with an Associate in Arts degree, I entered Concordia Seminary in St. Louis in September 1953. I lived in campus dormitories my first two years, with Luther Dau as my roommate. As I already wrote, I had come to know him better in my last year at Fort Wayne and we got along well together. Lu was from Aurora, Indiana, where his father was pastor for over 40 years. In the third year, Lu and I had a bed and study room in a seminary-owned, off the campus, apartment, that had common areas. With us were six other seminarians, including Ted Taykowski and Ted Klees. At the semester, Lu decided to get married and, because the seminary had not given its permission for his marriage, he dropped out of school. He returned in a few years and eventually became a pastor. He encountered troubles in his ministries, a good deal of them his own doing, and also his marriage ended in divorce. Due to heart and lung illness, he finally lived in a St. Paul, Minnesota, nursing home and he died in December of 1998. As he had requested of me in phone conversations during his last days, I preached the funeral sermon in the church of his youth in Aurora.

I was able to concentrate on my studies while at the seminary, though I did have a part-time job at Reed’s Drug Store in University City. I waited on customers at the cash register, served malts, shakes, and sodas from behind a soda fountain, and cleaned and restocked the store for the following day. Mr. Reed was a short, elderly man; gentle but firm, who had a younger assistant. I needed a typewriter and approached Mr. Reed for a loan to buy an Olympia (which is still around somewhere). He lent me the money without any interest, deducting a portion from my weekly pay. That typewriter had reams of paper run through it on which term papers and, later, sermons were typed.

I didn’t actually learn a great deal more of biblical doctrine at the seminary in St. Louis, because what was taught wasn’t much more than I had learned in the study of the catechism that Mr. Mueller had conducted in the school at Kodaikanal, India. I was taught Latin and Greek names for doctrines, such as Christology and soteriology (the study of salvation), all put together in systems. And I took Hebrew grammar the first year. What I did especially relish were the practical courses – how to conduct pastoral ministry. Students affiliated with a local parish as “field workers’ to gain some practical experience (though in my selected parish the pastor offered little) and also did some calling on patients in an assigned hospital. I also led some liturgies in worship at St. Paul’s Church in Kankakee during some summers. What I really yearned for was the first course in homiletics – sermon writing and preaching – but it wasn’t offered until the second year at the seminary. I was fortunate to have as my professor Dr. Richard Caemmerer, who gave me solid instruction for writing logical sermons that enable me to speak about our sinful condition, and, even more, the glorious message of God’s love and forgiveness, in and through Jesus. I preached my first sermon at Dad’s church, Holy Cross Lutheran in Wartburg, Illinois, on Easter Day, April 10, 1955.

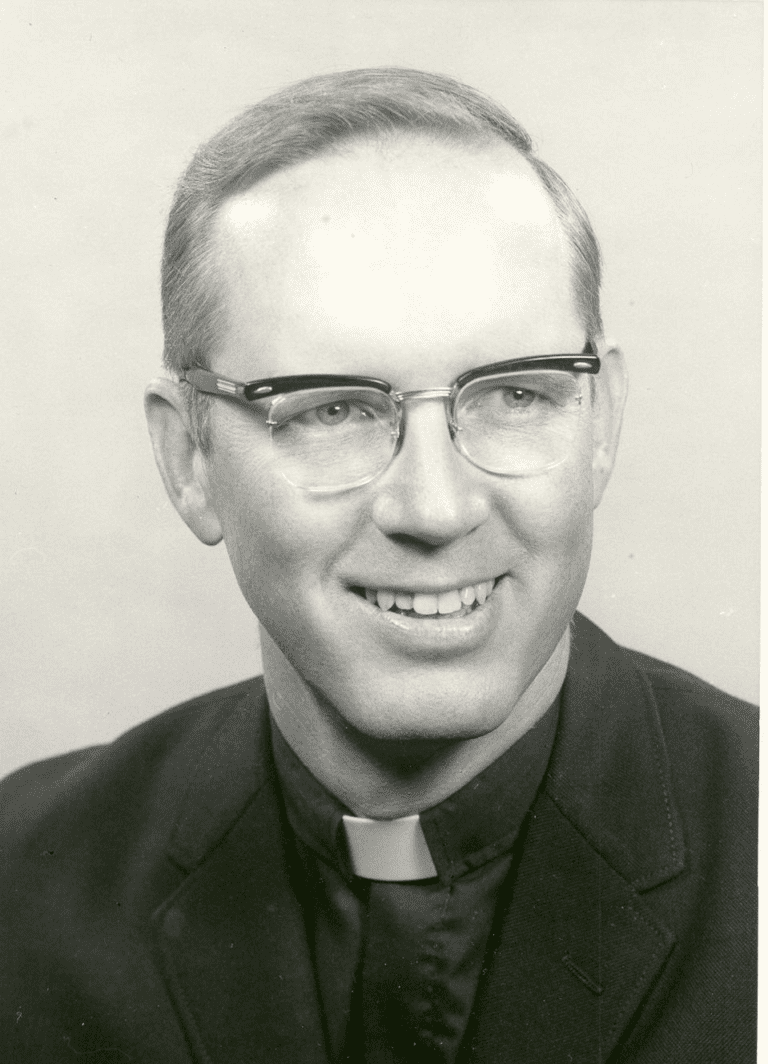

After two years at the seminary, I went through a graduation ceremony at which I received my Bachelor of Arts degree, having completed four years of college, the first two at Concordia, Fort Wayne. I then returned to the seminary the next fall for two more years of schooling; a total of six academic college years, interspersed with the year of vicarage (to which I referred previously) before the final year. “Vicar,” in its strictest sense, is a deputy, a substitute, such as “God’s vicar.” In the Church of England, it’s the title of the parish priest. The Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod has for years used “vicar” as the title for the seminary student who is assigned to a parish for one year of practical experience, supervised by its pastor (called behind his back “my bishop”). Thus a vicar was “on a vicarage” and a vicarage could be a great learning experience, or it could be a disappointment when the supervising pastor/bishop used his vicar just as a “gofer.” And that’s still true today.

Arlene was in St. Louis for a three month psychiatric affiliation at Bliss Hospital and so was present in April of 1956 when, at a special worship service, the vicarage assignments were distributed to the third year seminary class. My vicarage time turned out to be a year, that I never envisioned it would be, at St. Martin Lutheran Church in Clintonville, Wisconsin, where the pastor was Walter O. Speckhard. I almost couldn’t find Clintonville on an old Wisconsin map, because a fold of the map went through the name and it was hard to see. Clintonville, a community of 4,000, is 35 miles north of Appleton. Its largest industry is the Four Wheel Drive (FWD) Company, where heavy-duty trucks and fire engines are still manufactured. Before World War I, Walter Olen, its founder, had a good product, but didn’t promote it like Willy’s Jeep had its trucks, and so it wasn’t a huge enterprise. St. Martin had 2,000 members, with 1600 communicants; the third largest congregation in the North Wisconsin District of the LCMS. My vicarage was June 15, 1956, to the same date a year later.

Before I left for Clintonville, I did two things, major for me at that time. I purchased a ring and a car. A jeweler in St. Louis was kind to seminary students and allowed them time payments. I selected and bought an engagement ring and presented it to Arlene on my way to Clintonville. We planned the wedding for June of 1957. She had just started to work for Dr. Frank Land in offices, where Sarah Grubb (Klees) also worked, in the professional building west of the alley, at 160 West Rudisell Boulevard. Also, Dad and I went to a dealer in Waterloo, Illinois, and bought a car for use during my vicarage. It was a 1953 Chevy coupe; black, with 69,000 miles on it, and with no frills – manual shifting, no arm rests in the door, no turn signals. Dad helped me equip it with a turn signal kit that worked off of a small wheel affixed to the steering column. It turned as the steering wheel turned and, when the car was straightened out, it turned off the signal. The price of the Chevy was $650, and I was able to obtain a bank loan because I was going to make $200 a month as a vicar. That would pay for a ring and a car and my room and board during my vicarage. I arrived in Clintonville on Friday, June 15, 1956.

In those days, before a bypass was built, Highway 45 entered Clintonville from the south, at 8th Street took a left turn near the center of town, and that brought me to St. Martin Church, with its parsonage and parochial school to its west. The old church structure was rectangular, and a tall steeple, with bells in it, rose over a very small narthex. Its main floor seated about 450. There also was a balcony that housed the pipe organ and was available for the choir and more seating. A typical Lutheran altar dominated the small chancel. It had a tall backing of dark wood that contained a figure of Jesus with hands outstretched in blessing. There was only room for about twelve people at a time at the communion rail. The pulpit and lectern took up the rest of the space. Some years after I left St. Martin, the congregation erected a very modern sanctuary on the same site.

At the parsonage, Pastor Speckhard welcomed me into a small vestibule. Along its back wall was a door to the living room, another to his study, and the stairs to the second floor rose between them. A small desk faced the front wall. That was the church office. There his secretary, Viola Ebert, kept the congregation’s records, typed Sunday bulletins, and did the other tasks assigned to her. She was unmarried, probably because she was quite short with a hunched back; but she was very kind and very efficient. Pastor Speckhard had already been at St. Martin over 25 years, taking care of the large congregation by himself with the help of vicars, except for the year before I arrived. He was dressed in his distinctive garb that he always wore in public; a black suit, a white shirt with a winged collar, and a black bow tie. I soon found him to be a caring person, of deep theological convictions, a low-key, but excellent, preacher, a pastor who served his flock faithfully and tirelessly – too tirelessly it turned out. He and his loving and gentle wife had ten children, all well schooled. He was not given to possessions. He owned a Chrysler sedan that had been new in the late forties, but most of the time he walked about Clintonville, to its hospital and the homes of parishioners, using the car only for out of town trips.

After we became acquainted, Pastor Speckhard took me to the home of Esther Meister, a widow in her late forties. Her husband, Lawrence, known as “Smokey,” had operated the Cities Service oil franchise in town, and had recently built a new home for them on Clinton Street, two blocks from the church. They also owned a cottage on Pine Lake, five miles away. But in the year prior to my arrival in Clintonville, he suddenly had died of a heart attack, and she now was living only with her son Edward, a junior in high school. Daughter Audrey was at Oshkosh College and eldest daughter, Arline, a college graduate, was planning her marriage that summer to Ken Hippe. She and her children warmly received me. For the next year, Ed and I each had our own bedroom in the upstairs.

Esther had been reared on a farm and was a typical Wisconsin wife, who lovingly took care of her family as she cooked and cleaned, sewed and crocheted. While she hadn’t gone to high school, and had a quaint way of saying things from out of her German background, she was nobody’s fool. Smokey had left her with a good investment portfolio and she and her broker managed it well all of her days. I soon began to call her “Mutter” and she was indeed a second mother to me (and later Arlene) and another grandmother to our children. She was happy for my company and that I listened as she reminisced about Smokey, not incessantly, and as she expressed her feelings since his death. Our weekly ritual was watching The Lawrence Welk Show each Saturday night. She’d also have me drive her big, new Oldsmobile to go to Pine Lake, to sightsee, to pick up Audrey from college when she was to come home, or to take Ed to football games.

My duties at St. Martin were minimal at first. I was given a list of shut-ins to visit and was in charge of the youth group. I also taught the eighth grade confirmation class in the parochial school, as well as a few eighth graders that attended the public school; once a week after their school day. I seldom preached at St. Martin in the first months, as Pastor Speckhard liked to preach. He did, however, quickly arrange for a first preaching date in Wisconsin elsewhere – at a mission festival, because of my India experiences. It was on June 24, 1956, at Belle Plaine, in the country and held outside. I found that the breezes, though not real strong, threatened to blow away my manuscript, and I so I put a Bible on top of it and just went ahead and preached. Fortunately, I had worked hard in preparation and had no problem and, because of the occurrence, resolved not to use any manuscripts in the future. I followed through in that manner of preaching for years, spending every Saturday night in fervent study, functionally memorizing what I had typed out the week before, and then preaching the sermon, having full eye contact with the congregation.

Just about the time I was getting rather bored with visiting the same shut-ins over and over again, and preaching just a few times, my vicarage changed dramatically. I was informed in the first weeks of November that Pastor Speckhard had prostate problems and would have surgery in Valparaiso, Indiana, where his son Gerry taught at the university. The care of the congregation would be my responsibility during the weeks of his recovery. However, Pastor Speckhard never fully recovered. After the surgery (which was repeated twice in the next years) he entered into a deep depression that kept him from functioning. I dutifully visited my “bishop” every weekday morning, but I carried out all the pastoral duties, preaching almost every Sunday, eventually getting permission from the seminary to celebrate Holy Communion. The only thing I couldn’t do, because of the legality, was solemnize marriages (and nobody asked to be married that winter and spring.) While hospital calls were abundant, funerals, fortunately, were few. On Palm Sunday of 1957, I confirmed 42 eighth graders, following the St. Martin tradition as I conducted a two-hour service that included an oral examination of the class members.

I thoroughly enjoyed the vicarage experience during those final seven months. I don’t remember having any apprehension about taking on my added duties. I believe that’s because of how I was molded in the past. Arlene has said that the young men who had lived in India, and whom she came to know, were the most opinionated people she ever met. Opinionated, indeed! But I would add adventurous, assertive, and, yes, cocksure. I think that was because we were away from our parents at such a young age and had to fend for ourselves. I also was theologically well grounded and I knew the liturgy and church practices. And I took to heart Pastor Speckhard’s counsel, given very early: “Always be ready to admit when you’re wrong.” So I was open to guidance and constructive criticism. And, very importantly, I liked to be with people and usually got along fine with people of all social levels. And I’ve always been a talker.

My vicarage year came to an end on June 15, 1957. During it, I had written to the Dean of Students at the seminary and outlined how Arlene and I would manage our finances so that we could make it through my final year. Arlene would work at a hospital and I would again have a part time job at Reeds Drug Store. In those days students had to gain such permission, and it was extended to me. At least it was better than in my Dad’s seminary time when the students were practically forbidden female companionship. Besides letter writing and some phone calling, Arlene had visited me on a number of occasions in Clintonville, and she had kept me up to date on the arrangements she had made for our wedding. I left St. Martin with mixed feelings; somewhat sad to leave because I had formed such cordial relationships with many of the couples that were not that much older than I, but also looking forward to marriage and the last year of seminary. The congregation gave me an extra month’s salary to express their thanks for my “extra” services.