From My Mango Tree

by

Luther G. Strasen

(Updated in 2006)

The Auto-biography of Luther George Strasen

<>< <>< <><

Chapter Three – The Sapling

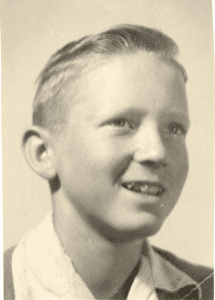

Until each of us was six years old, we lived in “the plains.” For us that was Nagercoil, and for the rest of the missionary children it was wherever their parents lived in the three mission districts. “The plains” was used by all to distinguish from Kodaikanal, also called Kodai, the beautiful settlement, over 7,000 feet up in the Palni mountains, about 200 miles north of Nagercoil. In 1914, the Mission Board had purchased a six acre compound called Loch End – Scottish for Lake End – with some buildings already on it. They eventually added a church, a school, a boarding home, and residences for vacationing missionaries. Since the months of July to August were the hottest and most humid in the plains, the school term in Kodai was from the middle of January into October, during which time we missionary children lived in the boarding school, allowing us to escape the heat and the insects, while our parents remained in the plains. In the last months of each year, when it was cooler in the plains, we rejoined our parents there and also celebrated Christmas with them. In the last months of 1939, after returning from the States, our family had settled into The Anchorage. If Dad and Mom experienced “empty nest syndrome,” it was at the next year’s January when I, the youngest, left home for schooling at Kodai, along with Betty, Ted, and Dave. During the nine months of school from 1940 to1945, I only saw Dad and Mom when they came up to Kodai for a month or so of vacation time. Polly and Ruth, of course, were at school in the United States.

So, in January of 1940, it was off to Kodai. The four of us, along with the rest of the missionary children from Nagercoil, boarded a bus that took us about 50 miles northeast to Tirunelveli, which was the closest station of the South India Railroad. I don’t remember any tears or homesickness. I had been to Kodai when Dad and Mom had vacationed there in my previous years and I was with my sister and brothers. It was a new adventure – school! At Tirunelveli we had a reserved train coach awaiting us. Each compartment had two bunks and windows that could be opened. Each coach also had a toilet room with a commode that emptied right out onto the railroad track. We were instructed not to use it while in the train station. The train headed for Kodaikanal Road Station, about 100 miles to the north. A missionary couple accompanied us and spent some of their time taking cinders out of our eyes that we acquired from the engine’s smoke, as we would hang our heads out of the windows to see down the track ahead. Upon arriving at Kodai Road, our car was put on a sidetrack so we could spend the night there. It was there that the rest of the missionary children, arriving on trains from Ambur and Trivandrum, joined us in their coaches. From our coaches we could see the station platform and the monkeys that climbed about the fences and on the station roof. The peddlers would come by, as they did at every station at which we stopped on the way, hawking their wares. “Pahlah kahpee” – milk and coffee, “Cigarette/beerdee” – cigarettes and a short, dark, leaf wrapped smoke, “Ahrungee parlum” – orange and fruit – they would call out along side the open windows of the coaches.

The 8,000 feet Palni Mountains rose abruptly from the plains about 25 miles from the Kodaikanal Station. The next morning we boarded the bus that would take us up to Kodai, to an elevation of 7,000 feet. The ghat road, (ghat being a mountain range in India) took many hairpin turns as it ascended. The road was narrow and not well guarded on the steep outer sides. Signs painted on flat rocks demanded, “Sound horn.” We always looked forward to seeing Silver Cascades, a tall waterfall alongside the road about two-thirds through the journey, and Perumal, a singular mountain that in the distance brooded over the area. Kodaikanal was first surveyed by the British in 1821 and became an ideal respite spot to get away from the heat of the plains and, especially, from mosquitoes and malaria. Because of its temperate climes, it was developed as an ideal place to school missionary children, as well as a vacation spot. A river had been dammed and a lovely lake had been formed, and the houses and compounds were built and developed on the slopes and hills above the lake. Farther away was the bazaar. In the early years, white travelers were carried up to Kodai on a “coolie path, so named because each traveler sat in an open canvas chair, suspended between poles on the shoulders of four Indian workers known as “coolies.” At some places the coolie path wasn’t much more than a yard wide and ascended precipitously. Its zig-zags could be seen from a vantage point in Kodai. Construction of the ghat road, which took a longer back route, was started in 1875, but was only completed in 1916. By my time in Kodai, the Europeans and Americans used the coolie path only to take a long hike.

We arrived in Kodaikanal at the Loch End compound. From its main entrance, above the residence on the left in the picture below, was a hedge-bordered road, which led directly to Mount Zion Church, built in 1932, which stood on a higher elevation. A series of broad steps ascended to the church, a sturdy structure with thick granite walls in Norman architectural style, cross shaped, with a bell tower.

Immediately to the right, below it under terraced walls, was Koehne Memorial School, completed in 1933, also built with granite. To the left of the school, as shown in the picture, was a landscaped rock garden, with ponds and flowers and an ivy-covered shelter, and to its right side was the large playground. Hidden by the church in the picture, on a slightly higher elevation, was the boarding home, also called Loch End. Another hedged drive curved up to it. Its original building was constructed in 1864. On the outer edges of the Loch End compound, below the boarding home and church and school, were four two-family residences where the missionaries lived during their four to six weeks of vacation from the heat of the plains. When Dad and Mom came to Kodai, we moved out of the boarding school and lived with them. The residences also had Scottish names; Lochnager, Afton (seen in the picture), Dunmere, and Oakland. A compound had also been purchased lower down on the Ghat Road called Trewin, which had residences called Trewin I & II, Conover, and Rozelle. During most of Dad and Mom’s vacation times we lived on the Loch End compound, but did reside once in Trewin I.

I remember many episodes at Kodai, but I’m not sure of the specific years. So I’ll just relate some of them. An initial incident, traumatic for me for a time, was my bed-wetting situation at the beginning of my first-grade year. Mrs. Alice Mueller was the wife of Mr. Kenneth Miller, the principal of the school, and together they were the “boarding parents.” I was wetting my bed at night and she was so displeased that she made me wear diapers, I now surmise, to shame me into stopping the wetting. In her defense, she was in her early twenties with two of her own children and was thrust into a setting far beyond her years of experience or her expectations. Well, the diapers didn’t work. I wet them the first night I wore them and never put them on again. Fortunately, I was sent to see Dr. Leckband, a physician for the missionaries, who told the Muellers that I was cold and needed more covers at night. That did the trick; but I was mortified for years that I had to wear diapers that one night. In my letters I simply state that I stopped wetting.

Even in the first grade, I was expected to write home once a week. I did so by dictating my thoughts to Betty until I could write for myself. Mother saved my letters and returned them to me, and now, almost 60 years later, I finally read them. They validate many of the experiences that follow and also express some of my values as well as my concerns. In one of my first letters, I wrote, (in Betty’s hand) “I am trying to be a good boy. Betty says I never kick, spit, or do anything like than any more.” At first my letters are addressed to “Daddy and Mother,” but as I grew older I started most of them with “Dear Parents.” Some of my early letters ended with “God bless and keep you” and when I was ten I wrote: “I always think of both of you and I hope God blesses and keeps you from all danger,” and a few weeks later, “I hope God blesses you with his greatest blessings.” In later letters, I often wrote at the end, “I don’t have anything more to right. Your son, Luther,” and the “right” even became “wright.” for a time. Another letter ends: “Lot’s of love. Well I’ve neared the bottom of the page.”

I was very interested in what was happening on the plains as well as relating what was going on in my life at Kodai. I wrote: “How is the hen? I hope it is not ded (sic)” and, a number of times, “How is the cat?” In a string of letters, I inquired about a pumpkin plant that had been planted before I left for Kodai. I constantly asked Dad and Mom to send articles that I had left in the plains, such as a Mickey Mouse book based on the ABCs, an automatic lead pencil, or a play truck. It’s apparent I knew they were about to come to Kodai for vacation time and I pestered them with “When?” And, of course, the letters are filled with recitations of what I did the week before I wrote, with whom I was rooming, what I did with my friends, what food we were served, and even the latest news of other missionaries and their children. I accompanied some of the letters with my artwork, almost like a comic strip, illustrating an event that I wrote about. I could even get a bit rebellious. Dad had written, with a little scolding, that we should have received some cards in the mail, even though we hadn’t. I responded: “We did not get your cards and I am not a scatterbrain.” Three of my great poetic works, still in my files, also were sent to the plains: “In Gethsemene” – with Harvey Knoernschild as a co-author,” The Pear Orchard,” and “The Wild West.” They are poems only a mother could love.

Two teachers conducted the Mission School; Mrs. Gertrude Heckel taught grades one to three and Mr. Mueller the upper grades. The school had two levels, with the primary grades on the first floor. Both levels had large windows that faced the playground. I learned well from Mrs. Heckel, especially how to read, and at the end of my first grade she advanced me to the third grade. But she also realized that I wasn’t learning the multiplication tables and, over a period of some weeks, had me come after school to her home at Dunmere to recite a number’s multiplications, on up to twelve. For that I‘ve been very thankful, even though I still don’t do well with higher mathematics. Mrs. Heckel lived by herself in Fort Wayne during her retirement years and she was a guest on occasion in our home with Mom and Dad in attendance. She came to both of their funerals and lived finally at Lutheran Homes until her death.

When I advanced to the fourth grade, in the upper level of the school, I was in a classroom setting of about thirty children. There were four rows of desks and each grade was in its own area so that its children could receive special attention when needed. Of course, we learned a great deal by hearing what was going on in the grades above us. The curriculum was the same as in an American school so that, even though outside of the school we lived in a different culture, when we came to live in the States we knew American money, history, geography, etc. At the back of the upper classroom, in a room separated by a door, was a library. The most memorable aspect of the library for me was its collection of The National Geographic, with magazines dating from the 1930s on up to the volumes that were being sent from the States at that time. I can still see in my mind the vivid drawing of an Egyptian pharaoh in the article “Daily Life in Ancient Egypt,” standing in his chariot pulled by two galloping horses, bow fully drawn to strike an enemy. Exciting! But even more engrossing was another article that had a picture of an Aztec priest standing at an open-air altar, offering up the heart just separated from the chest of a sacrificial victim.

Mr. Mueller was a kind man, but very disciplined. We respected him and didn’t disobey. He expected the best from us. One time, at the opening morning devotions, I felt sick and didn’t sing the hymn. Later he called me to his desk and reprimanded me. He also had a beautiful Palmer Method penmanship with many loops that he wanted us all to acquire. My penmanship was a disaster and he let me know so. My letters record me, at times, apologizing for my poor handwriting. In the sixth grade we were allowed to have ink in our desk inkwells and use dip pens, but the scratchy metal nibs didn’t help my cause. However, through the next years, even into high school, I continued to practice my penmanship and developed the looping capital letters that are in my signature today. The genesis of that style can be seen in many of my letters to Dad and Mom where, next to my signature, I’ve appended an LGS that begins with the L that loops down to the G and finishes with the S at the bottom. I was copying Dad, who had a brass seal, now in my possession, made of his BTS initials, with the S in the middle. He used it to mark sealing wax on packages he sent in the mail. In one of my letters I ask him to make a similar seal for me, even drawing the LGS in reverse, as it would have to be on the seal. He never said “Yes” and he never said “No.”

While Mr. and Mrs. Mueller were my first boarding home house parents, in time other missionaries took on that assignment. When I first arrived at Kodai, there were three dormitory areas with four or so children of the same age and gender in any one room. By July of 1942, a large new building was added with two-person bedrooms on the second floor and a first floor with a large dining room, an office, and rooms for the house parents and their children. The cooking was done by Indian servants and served by them. There was also an ayah by the name of Enah – a lovely in appearance, kind, Anglo-Indian, who cared for the younger children.

The children rated the house parents by how much they spanked. Mr. and Mrs. Sieving (we always called the missionaries “mister,” even though they were “reverends.”) didn’t spank; they were a caring couple and we enjoyed them. Mr. W. – I won’t use his name as I want to uphold the Eighth Commandment – used a rubber hose. Mr. S. (not Sieving), in 1944, was the worst. After supper of each weekday we would have a study time at the downstairs dining room tables. Mr. S. would early send those destined for a spanking to their rooms upstairs and soon we would listen to the swats and cries. It was also known that he would pull the girls dresses up, tighten their panties, and apply the hairbrush. My one spanking from him, in July 1944, came after a fight I had with Dick Bertram, unfortunately where Mr. S. could see us from his office. That night, Dick and I were sent upstairs early. I informed Mr. S. that Dick and I had “made up,” which we had, but that didn’t deter Mr. S. from applying the swats. I report that incident in a letter to Dad and Mom adding, “For some reason, I didn’t cry.”

I didn’t realize the extent of my feelings about Mr. S. until I read my letters again. Later that same July I wrote: “I like music lessons, but Mr. S. is too strict about practice,” and then reported that John Bertram had been spanked by Mr. S. because he forgot to practice or was late in doing so. I continued: “Because of this, I’m practicing as hard as I can. I suppose every one is in constant fear of him.” In September of 1944 I become more expressive. After writing that I was looking forward to the school term ending, I stated: “I just fear Mr. S. I don’t know, but every night it seems I’m going to get a spanking. I never really have a reason, but I just plain fear him.” Reading those sentiments now, I can just see Mom cringing in helplessness as she read my letter. During my seminary years, missionary S. was on the St. Louis campus taking some graduate work and I was tempted to confront him with not only his poor theology regarding reconciliation, but, even more, his inappropriate methods of discipline.

On the other hand, the one spanking I received from Mr. Mueller helped shape my life. As a seven year old, I roomed with two other boys, one being Dick Stelter. One night we were making noise instead of going to sleep and Mr. Mueller came in and warned us. But the third boy persisted and soon Mr. Mueller re-appeared and spanked him first. As he came to me, I told him that Dick and I weren’t guilty, but he still spanked us. The next morning, Mr. Mueller called us “innocents” into his study (a holy of holies in itself where two little guys stood before the “high priest”) and questioned us about the incident. He then proceeded to ask our forgiveness. He not only modeled repentance and forgiveness, but also impressed upon me my need as an adult to ask forgiveness from any person against whom I sin, and that includes any child.

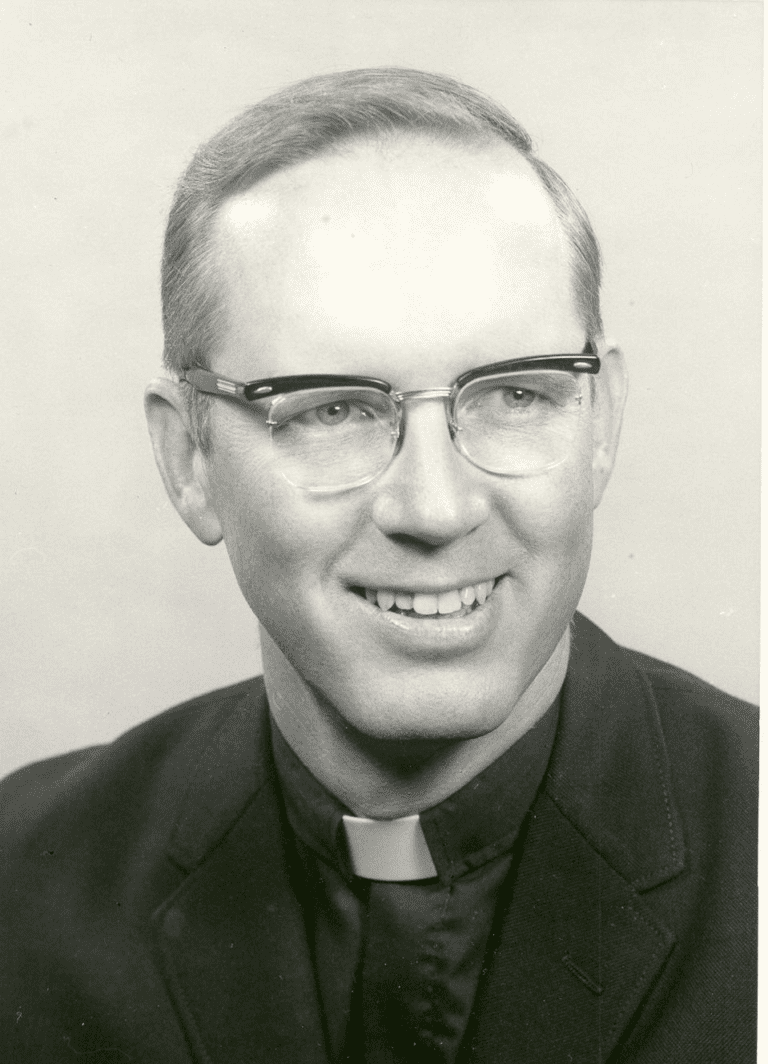

I also remember Mr. Mueller as the one who came up behind me while I was sitting at breakfast and put my first pair of glasses on me. I must have had my eyes examined in Nagercoil – I don’t recall that – where they found that I had severe astigmatism and ordered glasses for me, though they weren’t ready by the time school started. Thus glasses to this day. The last time I saw Mr. Mueller was at the LC-MS convention in Detroit in June 1971. He was visiting, as was I, and I enjoyed an hour or so talking with him. He died just a few years later, not at a great age.

The schedule at Kodai started with getting up, using the bathroom (if you think by now that I’m obsessed with toilets don’t be surprised that I now note that they were flush toilets), and making our beds. Breakfast was at seven, and then we were off to school, returning at lunchtime to the boarding home back up the hill. After school there would always be a four p.m. “tea-time,” with a glass of milk, a cookie or piece of cake. Before supper, which was at six, we would play around the compound or in our dormitory areas until a bell summoned us. Whether at recess or other times, we played softball, or games like “Pom Pom Pull-A-Way,” “Red Rover” (which resulted in some broken arms), “Kick the Can,” and “Pony Express.” The latter was more exercise than a game. Some of us would position ourselves around the compound and carry a message from one to the other, running as fast as we could. I loved to run and fancied that I was on a horse with the wind in my face. After supper on weeknights, we studied and then went to bed. During cold nights we would quickly undress, put on pajamas, and jump under the covers to get warm. Before falling asleep we often heard jackals calling to each other in the nearby hills and, sometimes, right under our windows, one would jolt us out of our sleep.

The morning of each Saturday in Kodai was a time for presenting our laundry, cleaning our rooms, and polishing our shoes. One afternoon a week was bath time, which consisted of washing the body while standing in a galvanized tub in which was some warm water. There was no heat in the room and, to this day, I think the worst form of punishment would be setting a person out in frigid weather in that same stance – a little warmth and great cold! The only fireplace in the boarding home to warm us in the cooler months was in the dining room. I never saw snow in India, but one morning there was frost on the grass and we all went out to inspect it.

Saturday evening was letter-writing time and that night we also received our church offering money. The basic Indian money is a rupee, which consists of sixteen annas. Mom and Dad put aside a fund for us children so that we would each have one rupee a month, of which we were to give two annas to church. So each Saturday I was given a two-anna coin to put in the collection at church the next day. I realized later that each month I was giving 50% of each rupee. That practice formed my giving habits for the years ahead, offering “first fruits” to God in thanks for His blessings.

The spanking and discipline might make it sound that Kodai was a most difficult time. It actually wasn’t, at least for me. The two spankings I described were my only ones and, aside from Mr. S., Kodai overall was an ideal setting, spiritually and physically. We had devotions every evening after supper. I enjoyed going to church at Mt. Zion. Already, when I was young, I knew the liturgies in The Lutheran Hymnal by heart and sang them with gusto, and I also came to memorize many hymn stanzas. I listened intently to the sermons. My letters are filled with reports of who preached on a Sunday, even with the text and the theme. And regularly I noted about some preacher: “I liked his sermon very much.” And here’s a real surprise! On March 14, 1945 I wrote: “Mr. S. preached again today. Whenever I hear him, I think of when I’ll be a pastor and how my sermons will be. I’m waiting for the day when I can use my voice in preaching God’s Holy Word.” We even were taught table manners and how to greet people. As I played about the compound and would see a missionary couple approaching me on their afternoon stroll, I would get ready to greet them. “Good afternoon, Mr. and Mrs. Stelter,” I would say. And they would respond, “Good afternoon, Luther.”

The morning of each Saturday in Kodai was a time for presenting our laundry, cleaning our rooms, and polishing our shoes. One afternoon a week was bath time, which consisted of washing the body while standing in a galvanized tub in which was some warm water. There was no heat in the room and, to this day, I think the worst form of punishment would be setting a person out in frigid weather in that same stance – a little warmth and great cold! The only fireplace in the boarding home to warm us in the cooler months was in the dining room. I never saw snow in India, but one morning there was frost on the grass and we all went out to inspect it.

Saturday evening was letter-writing time and that night we also received our church offering money. The basic Indian money is a rupee, which consists of sixteen annas. Mom and Dad put aside a fund for us children so that we would each have one rupee a month, of which we were to give two annas to church. So each Saturday I was given a two-anna coin to put in the collection at church the next day. I realized later that each month I was giving 50% of each rupee. That practice formed my giving habits for the years ahead, offering “first fruits” to God in thanks for His blessings.

The spanking and discipline might make it sound that Kodai was a most difficult time. It actually wasn’t, at least for me. The two spankings I described were my only ones and, aside from Mr. S., Kodai overall was an ideal setting, spiritually and physically. We had devotions every evening after supper. I enjoyed going to church at Mt. Zion. Already, when I was young, I knew the liturgies in The Lutheran Hymnal by heart and sang them with gusto, and I also came to memorize many hymn stanzas. I listened intently to the sermons. My letters are filled with reports of who preached on a Sunday, even with the text and the theme. And regularly I noted about some preacher: “I liked his sermon very much.” And here’s a real surprise! On March 14, 1945 I wrote: “Mr. S. preached again today. Whenever I hear him, I think of when I’ll be a pastor and how my sermons will be. I’m waiting for the day when I can use my voice in preaching God’s Holy Word.” We even were taught table manners and how to greet people. As I played about the compound and would see a missionary couple approaching me on their afternoon stroll, I would get ready to greet them. “Good afternoon, Mr. and Mrs. Stelter,” I would say. And they would respond, “Good afternoon, Luther.”

There wasn’t much organized entertainment at the boarding home. We didn’t gather around to sing. Even in school we had no children’s chorus, though Mr. Mueller at Lenten season once had us sing “Lamb of God, Pure and Holy” for a service, repeating the three similar verses without harmony. So, though I enjoy singing, I never was exposed to singing in harmonic parts and, still today, can’t read and immediately sing the bass section, as I hear others do. In India, we knew nothing of the songs that were popular in the States and, which, I found out when I returned to America, were sung each week on The Hit Parade radio program. Actually, I heard more classical music than anything else. On rainy days, Martin Wyneken would play the piano, and I came to recognize “Minuet in G,” “Largo,” “The Moonlight Sonata,” and other classical works. Mom had me take piano lessons in Kodai for a year, but I didn’t apply myself (despite Mr. S.) – and today wish I had.

While there were no American movies in Nagercoil, Kodai had a movie theater that screened recent American, as well as some English movies, and, according to my letters, I attended quite often. One of my letters in 1941 reports that I saw, as I spelt it, “The Wisard of Os.” It was the World War II years, and movies included “One of Our Aircraft Is Missing,” “Spitfire,” “From The Halls of Montezuma,” and “Mrs. Miniver.” Also I mention “Pinochio,” “Dumbo,” “Bambi,” “Snow White,” and Abbott and Costello movies. Each showing ended with a rendition of “God Save the King.” As a young lad, the movie that most impressed me was “Our Vines Have Tender Grapes,” with Margaret O’Brien, a quiet story about Swedish immigrants and an orphanage in Wisconsin. I saw it in the first months of 1945 when Dad and Mom were in Kodai. It’s the only film that I asked to go back and see again because it so touched me. Mom gave me the money to view it again.

While not entertained much by our boarding parents, instead entertaining ourselves more than anything else, we did have some planned activities. Kodaikanal nestles among higher elevations and, not far away from the town, are lovely waterfalls, sholas (wooded glens), and rock formations, to which we hiked as a group and where we ate the picnic meal that the servants had brought along. We would also stroll in a group around Coaker’s Walk, a promenade not far from the center of town, built into the mountain edge and providing a spectacular view of the plains below.

From 1941 to 1945, in the World War II arena, the Japanese had captured the territory of Burma, on the northeastern edge of India. The missionaries built some trenches on Loch End in case of air raids. But the only airplanes that flew over were friendly. The one effect of the war was some rationing. Of all things, toilet paper! One year the house parents came around each day and placed a ration of toilet paper sheets into each student’s top dresser drawer. We all hoarded them elsewhere in case of a special need some day. The missionaries also hosted some British and American soldiers on leave from their units. My letters make mention of these men, and I continued to write to a few and have their return letters. Each of us boarding children had an autograph book and mine has a number of entries from some of those men, some with artwork. One British airman drew a Spitfire fighter plane with Churchill’s words of praise, “Never has so much been owed by so many to so few.” Another soldier, visiting us in the plains, added a colored drawing of palm trees and a boat on a backwater.

In February of 1942, while we all were at school in Kodai, Dad and Mom told Betty and Ted that they would be journeying to the United States for their further schooling. Ted was in the seventh grade and Betty had just started her freshman year of high school at High Clerc. Betty recounts that they left Kodai with Missionary Rasch and his family, met Mom and Dad in Bombay to say farewell to them, and boarded the S. S. Wakefield that crossed the Indian Ocean to Cape Horn, South Africa, and then continued on to New York. World War II was raging, but they arrived safely, though their convoy did engage in some skirmishes in the Atlantic as they neared New York. The Rasch’s saw to it that they were put on a train to Chicago and from there they went to Milwaukee. No one met them on their arrival, but Betty had the wisdom to go to the home of the Sieberts who had been our neighbors on North 18th Street in 1938-39. Mrs. Siebert contacted Dad’s sister Frieda, a parochial school teacher in Milwaukee, who came to the house and informed them that she didn’t meet them because she couldn’t leave her teaching duties. Betty lived in Milwaukee with teacher Ebert’s family, Dad’s second cousin, and went to Zion school where he taught, essentially attending eighth grade classes, marking time before she would enter high school the next fall. Eberts wanted her to stay with them for her high school years, which she did for her freshman year, but she found them to be very restrictive. She wrote Dad and Mom in India and received permission to attend Concordia High School and College in River Forest, Illinois, for her sophomore year and live in a dormitory, and so joined Polly who was already there. Ted was directed to live with Dad’s sister Lydia and her husband Martin Koehler, who owned a pharmacy in Waseca, Minnesota. He finished the seventh grade and went on to the eighth in Waseca, spending the summers working on the farm of Fred Seeman, who was married to Dad’s sister Margaret. In 1943, Ted enrolled in high school at Concordia, St. Paul, Minnesota, Dad’s alma mater, living with our uncle and aunt, George and Agnes Dysterheft in St. Paul.

Betty and Ted’s departure left Dave and myself at Kodai. I didn’t hang around Dave very much, as he had his own set of friends. Personally, being away from my parents and brother and sisters didn’t harm my psyche. However, Dave and Ted, especially Dave, in later years expressed resentment. The arrangements made for Ted and my sisters when they arrived in the States to attend high school were stressful and, through the years, I’ve heard some comments of dissatisfaction from them. While Mom didn’t talk much about it, I know that she felt troubled, if not guilty, about the manner in which missionaries and their children had to be separated (and spanked by others?).

The time came for Dad and Mom to have another furlough. Their last furlough had ended in 1939 and they had been parted from four of their six children for most of those years. I had entered the seventh grade in January of 1945 and already in February I wrote in a letter: “I heard that we are going to America. That sure is good.” In subsequent letters I asked about an auction that Dad and Mom were having in the plains and I also asked about what I could sell of my (meager?) possessions in Kodai. It’s at this point that the Kodai letters came to an end. In June we were informed that our India family was scheduled to leave for the United States in July on a ship out of Bombay (now Mumbai). I’m not sure of all the details. I don’t remember returning to Nagercoil. Probably, Dave and I met Dad and Mom at the train station at Kodai Road, which was on the South India Railroad (SIR) line north to Madras (now Chennai), a large city a third of the way up the eastern side of India on the Bay of Bengal. The SIR was a narrow gauge line and the routes north of Madras were wide gauge. After arriving in Madras on the SIR, we transferred to the wide gauge station and boarded a train that headed northwest to Bombay, two-thirds up the western side of India on the Arabian Sea. Dad had reserved a private compartment for us and locked it when we came into the first stations. But a stationmaster further on unlocked it with a tool from the outside, and soon many more passengers piled in with us. Dad tried to resist the entry of the first man, a British soldier who pushed his suitcase ahead of him and kept calling Dad a “bloody fool,” but Dad finally had to give up the “battle” as more people climbed on. He shouldn’t have been surprised, because trains are India’s greatest transportation system and, with the immense population, there is little room for privacy when people urgently want to be on the train. The movie “Ghandi” depicts such overcrowding on trains, with scenes of even the roofs of passenger train cars covered with people on for the ride.

In Bombay, during the last week of June 1945, we joined up with other of our missionary families, including the Schroeders and Hattendorfs, to board the S.S Gripsholm, a Swedish ship. The World War II conflict with Germany had ended with its surrender in May of 1945, but the war with Japan continued. Sweden was a neutral country and so the ship was painted with a large Swedish flag and the words “Gripsholm” and “Sverig” – Sweden – on both of its sides. The same words were painted on the decks, and lights at night blazed down on all of it. A submarine or airplane could have seen the Gripsholm from miles away.

Dad and Mom and we two boys were assigned a cabin with no porthole, in one of the lowest decks. Each sidewall had two bunk beds, one on top of the other. The lavatory was down the corridor. As we left Bombay, we entered into a storm that lasted a number of days. At one time, when I was on the aft deck, the ship went into a large swell and I saw a huge wall of water behind the ship and high above me. Most of the passengers, including me, were seasick for a few days. I didn’t eat much more than hard Swedish crackers. Many slept on deckchairs to escape the heat of the cabins. Finally the storm abated and the weather was beautiful as we approached the Suez Canal. We docked at Port Said, the northern city on the canal, and then proceeded to Piraeus, Greece, the seaport of Athens. The docks there were heavily damaged from air raids and we remained on the ship. One of the sailors pointed out to me the Parthenon on the Acropolis, but without binoculars it was really too far away to see properly. As we left Greece, Dad talked to the ship’s purser and he moved our family to an upper deck cabin, with a large window looking out on the deck. From then on the trip, through the Mediterranean Sea, past the Rock of Gibraltar, and across the Atlantic Ocean, was delightful. Norm Schroeder and I enjoyed playing together, even going to a lower deck to find the entry door in the foremast. We climbed inside of it and proceeded up a ladder. High up on the mast was the opening to the crow’s nest. A sailor who was on watch greeted us and made sure that the ship officers on the bridge, that was behind and below us, couldn’t see us.

In early August we entered New York harbor and I saw the Statue of Liberty for the first time in my remembrance. After docking and getting through customs late at night, we stayed with a Lutheran family for a few days until we boarded a train to Chicago. As the Pennsylvania Railroad train traveled through Fort Wayne, right where the tracks cross Broadway at the GE plant, Norm Schroeder told me that his family once had relatives in Fort Wayne. The factory building remained in my memory. Little did I realize that I would return to Fort Wayne.

Upon arriving in Chicago, we stayed at Pastor Erwin Meinzen’s home for a few days. He

had come to India in 1921 with Dad and they were good friends. Meinzen spent the war

years in Chicago as a pastor of a parish and then returned to India until he retired. It was at the Meinzen home, on August 6, 1945, that I read in The Chicago Tribune about the explosion of the first atom bomb over Hiroshima, Japan. From the Meinzens we went to Concordia Teachers College (CTC) in River Forest, Illinois, where we were given beds in the school’s student dispensary. Pauline was about to enter her last year at CTC and Betty had been in its high school department. On August 14, 1945, as I walked across the college’s football field, I heard sirens, which I soon learned were sounding to celebrate the news that Japan had accepted the surrender terms of the allied forces.

Housing was at a premium as World War II came to an end, but a house for rent was located in Elgin, Illinois, at 440 Ann Street, and we moved there from the college before the school year began. The house was roomy enough, with Dad and Mom’s bedroom downstairs, along with a living room, dining room and kitchen and half-bath. More bedrooms and a full bath were on the second floor. All the furniture was second hand. Ted enrolled as a senior and Dave as a freshman at Elgin High School and I entered the eighth grade at the parochial school of St. John’s Lutheran Church in downtown Elgin.

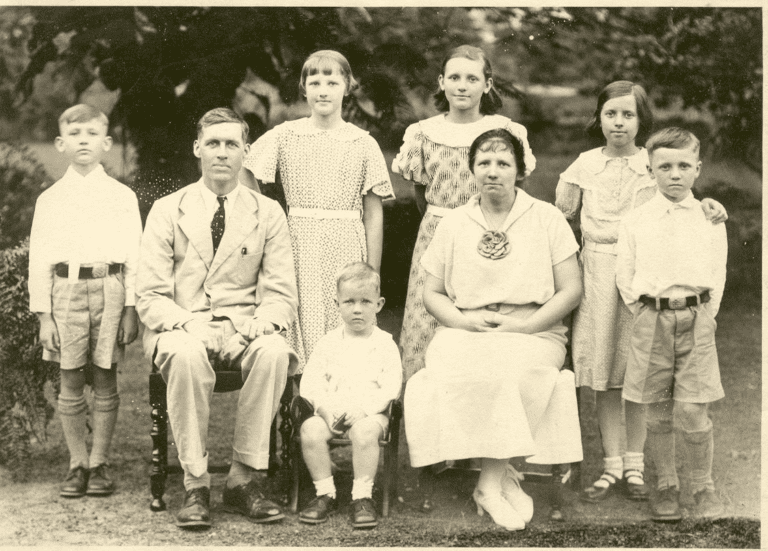

The above picture was taken in Elgin in the spring of 1946. Polly, on the left, was still at Concordia Teacher’s College (CTC), studying to be a teacher. Betty was working as a waitress, engaged to be married to Fred Nohl, who was also at CTC. Ruth was attending Valparaiso University in Indiana. Ted, Dave, and I were in school, as detailed above. As Mrs. Heckel skipped me through second grade and I took only half of the seventh grade in India, I turned twelve years old that September and would just turn thirteen when entering high school the following year. The seventh and the eighth grades were in one room at St. John’s, with about fifteen students in my eighth grade. Up to that time, I had never taken God’s name in vain or used vulgarity. However, during the first days of school, an eighth grade boy said things that I hardly believed I had heard. Sadly, I learned quickly to say the same things and eventually I was chastened by a classmate, Ruth Smith, who confronted me with my wrongdoing.

Mr. Schaeffer was my eighth grade teacher and I think he didn’t know what to do with me. Because of my excellent education in India, even at my age I was scholastically ahead of my classmates. I must have been somewhat of a discipline problem for Mr. Schaeffer, because I spent some times in the hall and he even had me spend some school afternoons painting a fence on the playground. Pastor Werfelmann taught confirmation classes on school mornings, and that also was easy because I had already memorized the catechism in India. I was confirmed on Palm Sunday, 1946. At graduation I was the salutatorian of the class (why such designations in grade school?) and that dictated that I give a speech at the graduation exercises. I wrote and memorized it and spoke it well – until I got to the final sentence, when my mind went blank. I stood before the assembly for the proverbial eternity; then the sentence came back to me and I said it and sat down.

While in Elgin during the fall of 1945, Dad did some lecturing about India. One day he was gone for a lecture trip and I had an incident at school that caused Mom a great deal of stress. The stairwell to the basement of the school had some water pipes that crossed overhead at the bottom of the steps. I regularly jumped up to them from the last lower steps, swung out on them and landed on my feet. That day I jumped and missed and fell, hitting the back of my head on the concrete floor. All I remember is telling Ruth Smith what had happened, and the next thing I knew I was in a hospital bed. I had walked home, about a mile, and had come into the house talking nonsense. Mom had no idea what had happened and got me to the hospital, where I recovered from the concussion.

In January of 1946, Dad was asked to be the pastor of St. Mark Lutheran Church in New Germany, Minnesota, to spell its pastor for a year while he recuperated from an illness. Dad went to New Germany, while we stayed in Elgin to complete the school term. That next summer, Mom, Ted, Dave, and I moved to New Germany and lived in the furnished parsonage.

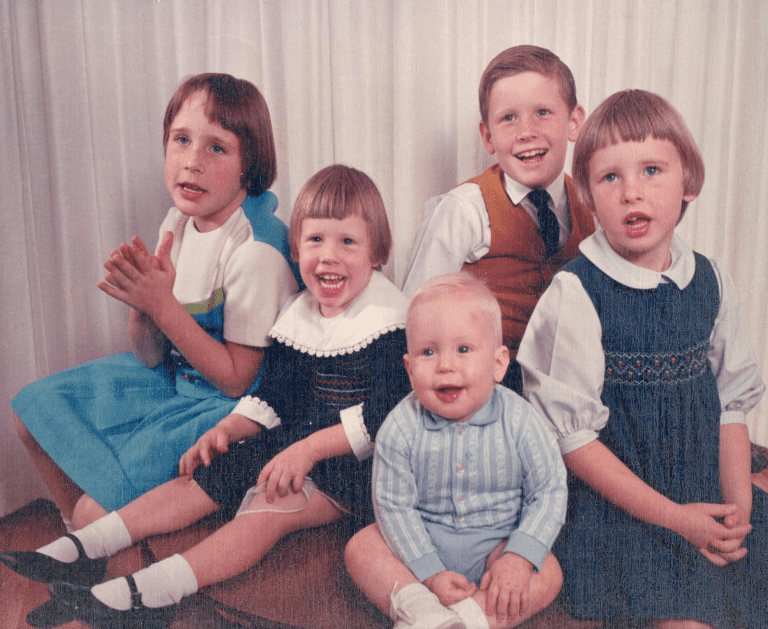

Ruth and Betty also joined the family for some of the summer. This picture was taken in New Germany. The town is about 40 miles due west of Minneapolis in Carver County, which is populated predominately by Missouri Synod Lutherans – so much so that today it has its own Lutheran high school at Mayer, Minnesota. New Germany has changed little, as apparent from a visit in August, 2002. It still has a main street, about six blocks long, which runs east and west, paralleling a railroad track to the south and two more streets to the north. There are a number of taverns and stores on it. The church, parsonage, and school grounds are at the east end of the main street.

One day that summer, Dad asked me whether I still wanted to be a pastor. I had never wanted to be anything else and I answered in the positive. He told me that I would then be attending Concordia High School and Junior College in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Dave would also attend there, starting as a sophomore in high school, but not to study for the ministry. The two of us, accompanied by Polly, who went on to her first teaching job at the Detroit Deaf Institute, traveled to Fort Wayne in September of 1946. Dave and I returned to New Germany by Greyhound bus to be with Dad and Mom that Christmas. Two months later, in February of 1947, they returned to India.